Issue 99: Copyright for Generative Artificial Intelligence (ChatGPT, DALL·E 2, and the like)

This week we look at the intersection of the hot topic of artificial intelligence (AI) and copyright law. Can works created by an AI algorithm be copyrighted? Do the creators of AI models have an obligation to respect the copyright of works they use in their algorithms?

The rush of new AI tools to the public has quickly inflamed these questions. There seems to be little doubt that the output of AI algorithms cannot be copyrighted. There is little clarity about the legality of AI algorithms using copyrighted material.

- Copyright is for humans

- Copyright Office rejects AI Art

- What is a "large language model" (LLM) artificial intelligence system?

- How do LLMs work with images?

- Models of unimaginable complexity

- Getty Images goes after Stable Diffusion

- Maybe it isn't so magical after all?

- Open source coders sue GitHub owner Microsoft and Microsoft's partner OpenAI

There is really much more to be said on the topic, but this will do for one Thursday Thread. Let me know if you have seen other angles that you think should be more broadly known.

Feel free to send this newsletter to others you think might be interested in the topics. If you are not already subscribed to DLTJ's Thursday Threads, visit the sign-up page. If you would like a more raw and immediate version of these types of stories, follow me on Mastodon where I post the bookmarks I save. Comments and tips, as always, are welcome.

Copyright is for humans

We must determine whether a monkey may sue humans, corporations, and companies for damages and injunctive relief arising from claims of copyright infringement. Our court’s precedent requires us to conclude that the monkey’s claim has standing under Article III of the United States Constitution. Nonetheless, we conclude that this monkey—and all animals, since they are not human—lacks statutory standing under the Copyright Act.

It might be useful to start here—copyright is recognized as a protected right for humans only. In this case, PETA argued on behalf of a selfie-snapping Indonesia monkey named Naruto that the monkey held the copyright to an image. (Slater, a photographer, left his equipment unattended, and Naruto snapped this picture.) The court held "that the monkey lacked statutory standing because the Copyright Act does not expressly authorize animals to file copyright infringement suits."

Discussion of whether the output of a generative AI system can itself be copyrighted hinges around Naruto v. Slater, and most everyone I've read said that the result of an algorithm similarly can't be copyrighted.

Copyright Office rejects AI Art

The US Copyright Office has rejected a request to let an AI copyright a work of art. Last week, a three-person board reviewed a 2019 ruling against Steven Thaler, who tried to copyright a picture on behalf of an algorithm he dubbed Creativity Machine. The board found that Thaler’s AI-created image didn’t include an element of “human authorship” — a necessary standard, it said, for protection.

As expected, the U.S. Copyright Office rejected an application for a work from an algorithm. In fact, the Copyright Office has started the process of revoking a previously granted copyright for an AI-generated comic book.

I'm starting here because it is helpful to know whether the output of an AI system can be copyrighted when we later look at the use of copyrighted sources in AI.

What is a "large language model" (LLM) artificial intelligence system?

LLMs are generative mathematical models of the statistical distribution of tokens in the vast public corpus of human-generated text, where the tokens in question include words, parts of words, or individual characters including punctuation marks. They are generative because we can sample from them, which means we can ask them questions. But the questions are of the following very specific kind. “Here’s a fragment of text. Tell me how this fragment might go on. According to your model of the statistics of human language, what words are likely to come next?

The type of artificial intelligence that has been of great interest recently is classified as "large language model". Simplistically: they analyze tremendous amounts of texts—the entire contents of Wikipedia, all scanned books that can be found, archives of Reddit, old mailing lists, entire websites...basically, anything written on the internet—and derive a mathematical model for determining sequences of words. Then, when fed a string of words as a prompt, it looks at the statistical model to see what comes next. (Powerful stuff! I recommend reading Shanahan's 12-page arXiv paper to get a fuller sense of what LLMs are about.)

We see the output of that in text form with ChatGPT. But what about the image-generating systems?

How do LLMs work with images?

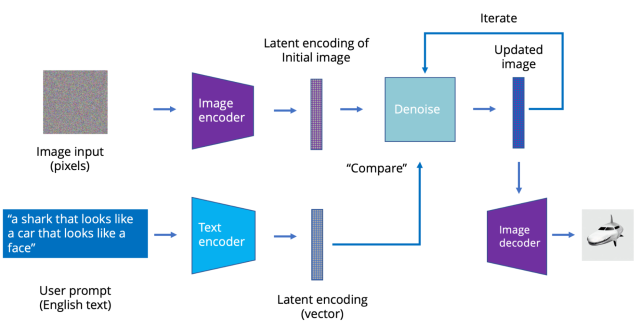

The latest image models like Stable Diffusion use a process called latent diffusion. Instead of directly generating the latent representation, a text prompt is used to incrementally modify initial images. The idea is simple: If you take an image and add noise to it, it will eventually become a noisy blur. However, if you start with a noisy blur, you can “subtract” noise from it to get an image back. You must “denoise” smartly—that is, in a way that moves you closer to a desired image.

In image form, the linking of text descriptions of images found on the internet (such as found in HTML "alt" attributes or in the text surrounding the image in a catalog) is what the algorithm uses to generate new images.

So, going back to Naruto v. Slater, we're pretty sure that the output of these algorithms and statistical models can't be copyrighted. But were the copyright holders' rights violated when their text and images were used to build the statistical models? That is the heart of the debate happening now.

Models of unimaginable complexity

Given that LLMs are sometimes capable of solving reasoning problems with few-shot prompting alone, albeit somewhat unreliably, including reasoning problems that are not in their training set, surely what they are doing is more than “just” next token prediction? Well, it is an engineering fact that this is what an LLM does. The noteworthy thing is that next token prediction is sufficient for solving previously unseen reasoning problems, even if unreliably. How is this possible? Certainly it would not be possible if the LLM were doing nothing more than cutting-and-pasting fragments of text from its training set and assembling them into a response. But this is not what an LLM does. Rather, an LLM models a distribution that is unimaginably complex, and allows users and applications to sample from that distribution.

Returning to Shanahan's paper (see, I told you it was worth reading), we learn that the algorithms are more than just copy-and-paste. That is what makes them seem so magical. Is that magic creating a new derivative work?

Most of the lawsuits probing this question seem to be happening with images and software code. For example, this one from Getty Images.

Getty Images goes after Stable Diffusion

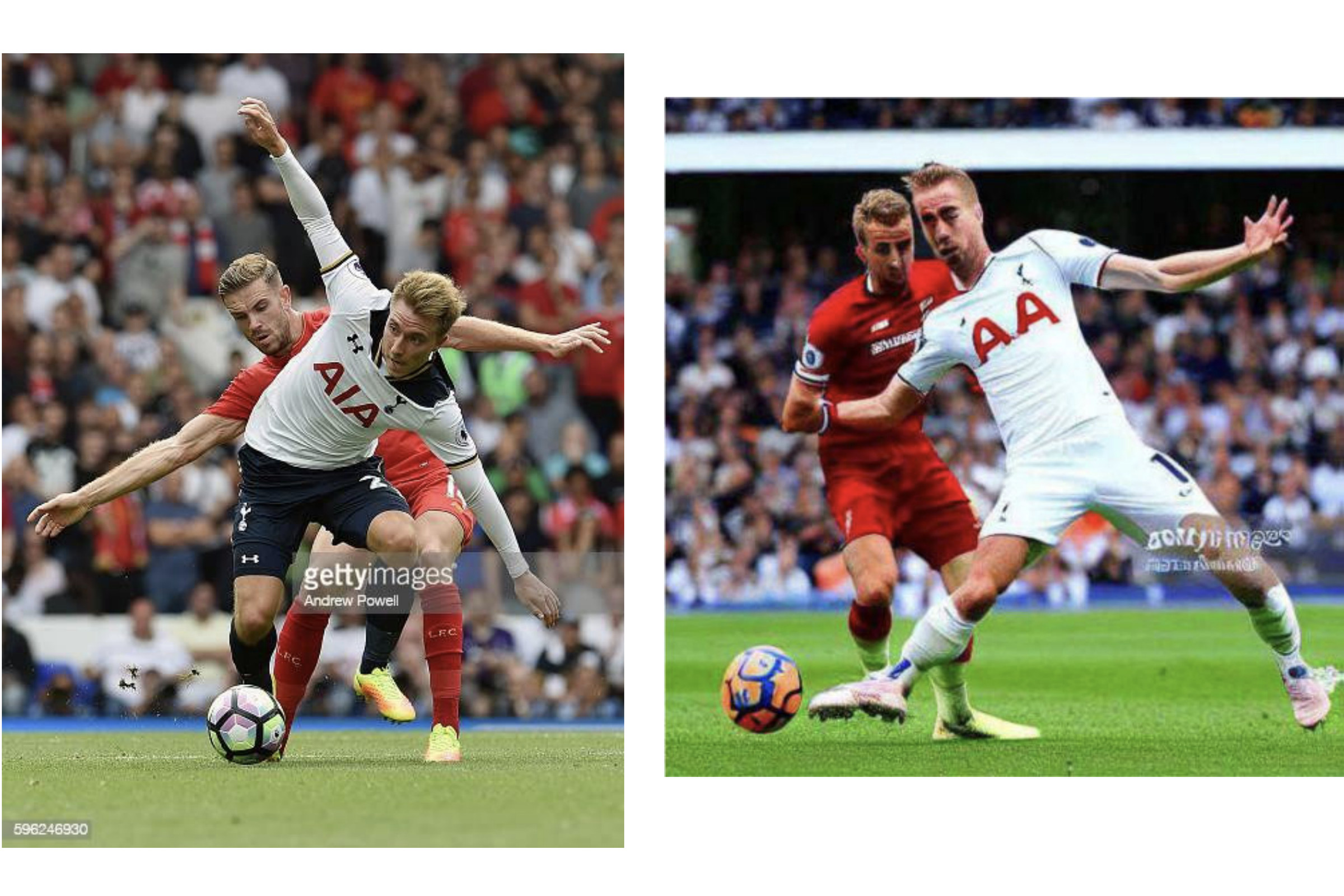

[Getty Images] is accusing Stability AI [creators of the open-source AI art generator Stable Diffusion] of “brazen infringement of Getty Images’ intellectual property on a staggering scale.” It claims that Stability AI copied more than 12 million images from its database “without permission ... or compensation ... as part of its efforts to build a competing business,” and that the startup has infringed on both the company’s copyright and trademark protections.

A rich source of images and descriptions about images can be found in the Getty Images catalog.

The algorithm is so uncanny that it reproduces what looks like the Getty Images watermark in the derived image. Getty Images alleges three things.

- Removed/altered Getty Image's "copyright management information" (the AI-generated visible watermark resembles that of Getty Image, so these photos must have been taken from them)

- False copyright information (modification of the photographer's name)

- Infringing on trademark (a very similar watermark implies Getty Images affiliation)

The case is in front of the U.S. District Court in Delaware.

Maybe it isn't so magical after all?

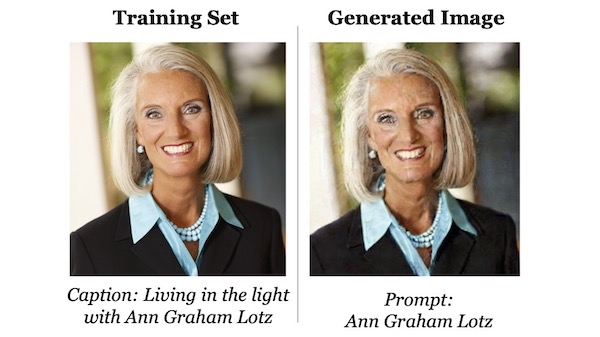

Popular image generation models can be prompted to produce identifiable photos of real people, potentially threatening their privacy, according to new research. The work also shows that these AI systems can be made to regurgitate exact copies of medical images and copyrighted work by artists. It’s a finding that could strengthen the case for artists who are currently suing AI companies for copyright violations.

This article summarizes the finding of researchers investigating whether it was possible to get the LLM algorithms to return known images in the dataset. With a unique enough prompt and training data set: yes, that seems quite possible.

Open source coders sue GitHub owner Microsoft and Microsoft's partner OpenAI

Two anonymous plaintiffs, seeking to represent a class of people who own copyrights to code on GitHub, sued Microsoft, GitHub and OpenAI in November. They said the companies trained Copilot with code from GitHub repositories without complying with open-source licensing terms, and that Copilot unlawfully reproduces their code. Open-source software can be modified or distributed for free by any users who comply with a license, which normally requires attribution to the original creator, notice of their copyright, and a copy of the license, according to the lawsuit.

Microsoft bought GitHub in 2018 and Microsoft is a major investor and user of OpenAI's LLM technology. Copilot is a new feature in GitHub that generates code snippets based on the open source code files uploaded to GitHub and a prompt from the user. (Sound familiar?) The software developers claim that Microsoft's use of the code files violates the terms of open source license agreements. This is a new case, and it is one to watch to see how copyright and license terms intersect with large language models.

Roaar?

A man and his cat. Is there any more to life?