On March 16, 2023, I gave a presentation with this title to the code4lib conference in Princeton, New Jersey.

The suggested links from the end of the presentation are listed below followed by a rough transcript of the talk.

As I noted in the talk, the judge in the Hachette et al v. Internet Archive lawsuit has scheduled a hearing for Monday, March 20 at 1pm Eastern U.S. time.

The Internet Archive has a blog post with details about how to listen in.

Suggested Links

Presentation Transcript

Presentation slide 1: Title Slide

Some disclaimers—I am not a lawyer and this is a litigious area; we'll get into that at the end of the talk. I believe the legal grounds for CDL are sound and resonable, but those grounds have not yet been adjudicated in court. Before you embark on a CDL program, be sure to gauge your library’s risk tolerance and make choices that are reasonable for your institution. You probably want to get your legal council involved.

Presentation slide 1: Title Slide

Some disclaimers—I am not a lawyer and this is a litigious area; we'll get into that at the end of the talk. I believe the legal grounds for CDL are sound and resonable, but those grounds have not yet been adjudicated in court. Before you embark on a CDL program, be sure to gauge your library’s risk tolerance and make choices that are reasonable for your institution. You probably want to get your legal council involved.

Second, I'm leaning heavily into a NISO working group's work product. The Interoperable Systems for Controlled Digital Lending working group is funded by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon foundation to NISO in 2021. The working group expected to have a draft for public comment out right about now when I proposed the talk, but it isn't quite there yet.

Describing CDL

Presentation slide 2: What is Controlled Digital Lending?

In a nutshell, Controlled Digital Lending is Interlibrary Loan or Course Reserves meets Digital Rights Management. The core idea is that the library exchanges physical lending with digital lending. And so CDL has these three key characteristics:

Presentation slide 2: What is Controlled Digital Lending?

In a nutshell, Controlled Digital Lending is Interlibrary Loan or Course Reserves meets Digital Rights Management. The core idea is that the library exchanges physical lending with digital lending. And so CDL has these three key characteristics:

- a strict adherence to the number of physically owned copies of a work being never greater than the sum of simultaneous physical uses and digital uses. This is known colloquially as the "Own-to-Loan" ratio. If a physical copy is owned, then that physical copy may be lent either physically or digitally. Keep this concept in mind—I'll refer back to it several times in the presentation.

- controls that limit access to materials to authorized library patrons

- user interface elements that limit the potential of unauthorized distribution of digital surrogates. This is a fundamental part of the trust relationship between libraries and intellectual property holders.

CDL is grounded in these three points—characteristics that make CDL as close as possible to the physical, legal, and economic conditions that libraries use now to lend items.

Six workflow components

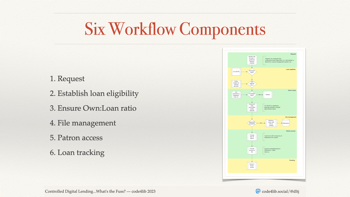

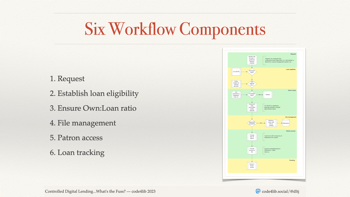

Presentation slide 3: Six Workflow Components

So let's take a step back and look at the big picture. There are six steps to the CDL workflow: request, establish loan elibibility, ensure the Own:Loan ratio, file management, patron access, and loan tracking. And with each of these components there are a variety of standards and options that could be used. The workflow steps are stacked in this diagram, and we're going to take a peek at each one.

Presentation slide 3: Six Workflow Components

So let's take a step back and look at the big picture. There are six steps to the CDL workflow: request, establish loan elibibility, ensure the Own:Loan ratio, file management, patron access, and loan tracking. And with each of these components there are a variety of standards and options that could be used. The workflow steps are stacked in this diagram, and we're going to take a peek at each one.

Request

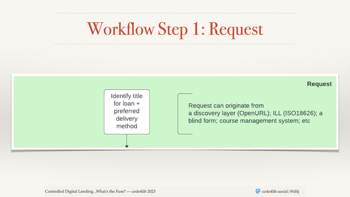

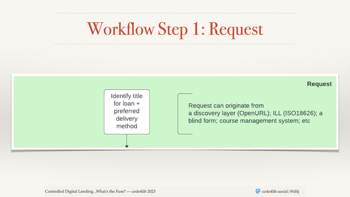

Presentation slide 4: Workflow step 1 — Request

First is the request stage—when the patron tells the library what they want. This can come from a request button in a discovery layer or catalog, a blank form, or an OpenURL from another system. And this would have all of the metadata you would expect: details about the item, the context of the patron identity, any special notes about the request, etc.

Presentation slide 4: Workflow step 1 — Request

First is the request stage—when the patron tells the library what they want. This can come from a request button in a discovery layer or catalog, a blank form, or an OpenURL from another system. And this would have all of the metadata you would expect: details about the item, the context of the patron identity, any special notes about the request, etc.

Establish loan eligibility

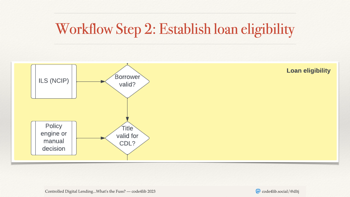

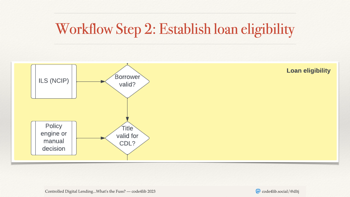

Presentation slide 5: Workflow step 2 - Loan eligibility

When the request comes in, the first thing the CDL system needs to do is determine if the user is eligible to receive the item and if the item is eligible to be lent through CDL. Understanding if the user is eligible is pretty straight forward: are they a valid member of your community (resident, student, staff, etc.). Looking at the eligibility of the book is where we get into our first risk factor. Some libraries have, for instance, decided that books published within a 5-year moving wall are not eligible for CDL...that to lend a more recently published item may have an economic impact on the publisher. I believe the Internet Archive's CDL program operates with such a restriction.

Presentation slide 5: Workflow step 2 - Loan eligibility

When the request comes in, the first thing the CDL system needs to do is determine if the user is eligible to receive the item and if the item is eligible to be lent through CDL. Understanding if the user is eligible is pretty straight forward: are they a valid member of your community (resident, student, staff, etc.). Looking at the eligibility of the book is where we get into our first risk factor. Some libraries have, for instance, decided that books published within a 5-year moving wall are not eligible for CDL...that to lend a more recently published item may have an economic impact on the publisher. I believe the Internet Archive's CDL program operates with such a restriction.

Ensure Own:Loan ratio

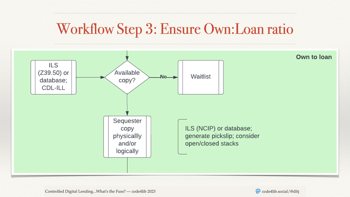

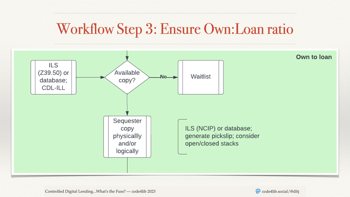

Presentation slide 6: Own-to-loan

Next, is there a physical copy that can be sequestered while the digital loan is happening? This is the Own:Loan ratio—can the library ensure that there is one user of the item it has purchased. This can take several forms: perhaps a library treats this like a hold request—they print a paging slip, retrieve the item from the open stacks, and put it on a shelf in the back room. Or maybe the library has closed stacks—something like a high-density storage system—and it marks the item as unavailable in the ILS. Maybe a library bought several physical copies and keeps them in a warehouse so it has a pool of items that can be lent out via CDL. Whatever the library decides its risk tolerance is, this is where it is implemented. A wait-list can also be added at this step in case all of the eligible copies are loaned out.

Presentation slide 6: Own-to-loan

Next, is there a physical copy that can be sequestered while the digital loan is happening? This is the Own:Loan ratio—can the library ensure that there is one user of the item it has purchased. This can take several forms: perhaps a library treats this like a hold request—they print a paging slip, retrieve the item from the open stacks, and put it on a shelf in the back room. Or maybe the library has closed stacks—something like a high-density storage system—and it marks the item as unavailable in the ILS. Maybe a library bought several physical copies and keeps them in a warehouse so it has a pool of items that can be lent out via CDL. Whatever the library decides its risk tolerance is, this is where it is implemented. A wait-list can also be added at this step in case all of the eligible copies are loaned out.

File management

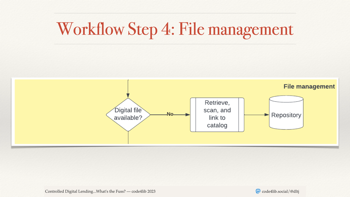

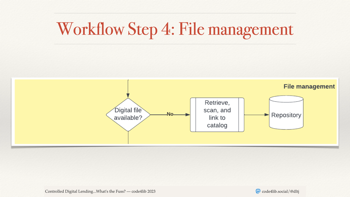

Presentation slide 7: File management

Next, the library has to have a digital scan of the item that they can lend out. If a library doesn't have a digital copy of the item, then that is a whole workflow itself. Maybe it scans the item itself. Maybe it gets a copy from a consortium partner that has already digitized it. Somehow we'll need to determine if we have a digital copy and have a way to make one if we don't. We'll probably also want to keep a digital copy once we've made one in case someone else asks for it again, but that, too, is part of the risk management strategy.

Presentation slide 7: File management

Next, the library has to have a digital scan of the item that they can lend out. If a library doesn't have a digital copy of the item, then that is a whole workflow itself. Maybe it scans the item itself. Maybe it gets a copy from a consortium partner that has already digitized it. Somehow we'll need to determine if we have a digital copy and have a way to make one if we don't. We'll probably also want to keep a digital copy once we've made one in case someone else asks for it again, but that, too, is part of the risk management strategy.

Patron access

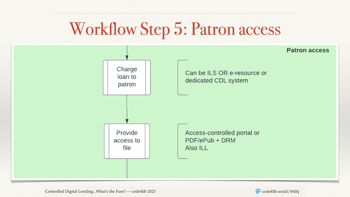

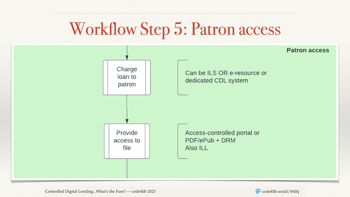

Presentation slide 8: Patron access

Now we have something to get into the patron's hands. This is the digital equivalent of wanding the barcode and checking out the item to the patron. We may use some sort of digital rights management—or DRM—that locks this file to this user for a specific period of time. Adobe Digital Editions software is commonly used for this, although there are other alternatives. This might mean the user needs some specialized software to read the file. Or the library might opt for an only-online experience such as an IIIF viewer that has the clipping and downloading functionality removed. During the pandemic, Fordham University whipped up a quick system that uses Google Drive restrictions to allow a specific Google Workspace user to read but not download/print a PDF for a specific period of time. There are some interesting possibilities here.

Presentation slide 8: Patron access

Now we have something to get into the patron's hands. This is the digital equivalent of wanding the barcode and checking out the item to the patron. We may use some sort of digital rights management—or DRM—that locks this file to this user for a specific period of time. Adobe Digital Editions software is commonly used for this, although there are other alternatives. This might mean the user needs some specialized software to read the file. Or the library might opt for an only-online experience such as an IIIF viewer that has the clipping and downloading functionality removed. During the pandemic, Fordham University whipped up a quick system that uses Google Drive restrictions to allow a specific Google Workspace user to read but not download/print a PDF for a specific period of time. There are some interesting possibilities here.

Loan tracking

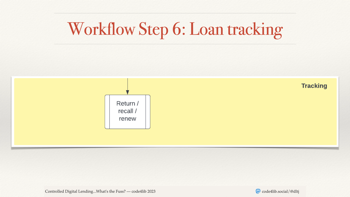

Presentation slide 9: Tracking

Finally, we need a way of recording the loan and keeping statistics to show that the library has kept in compliance with the Own:Loan ratio. The patron might also elect to return the item early. There might also be a notion of a recall for an item that was checked out with an extended due date. All of the kinds of tracking and item management that libraries do for physical items probably have an equivalent need in a CDL environment.

Presentation slide 9: Tracking

Finally, we need a way of recording the loan and keeping statistics to show that the library has kept in compliance with the Own:Loan ratio. The patron might also elect to return the item early. There might also be a notion of a recall for an item that was checked out with an extended due date. All of the kinds of tracking and item management that libraries do for physical items probably have an equivalent need in a CDL environment.

Four architectural models

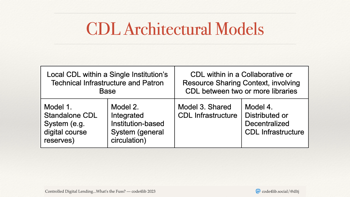

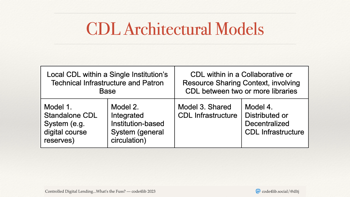

Presentation slide 10: CDL Architectural Models

So we have these for six workflow steps: the request, establishing loan eligibility, ensuring the Own:Loan ratio, getting the digital file, providing that file to the patron, and tracking the loan. As you think about systems that mimic these six steps, the kinds of architecture generally fall into four buckets. The first two are within an institution: an institution's own items with an institution's own patrons. The second two involve controlled digital lending on a collaborative scale—where the owning library is different from the patron's library. Let's take these in turn and see what the impact is on the six workflow steps.

Presentation slide 10: CDL Architectural Models

So we have these for six workflow steps: the request, establishing loan eligibility, ensuring the Own:Loan ratio, getting the digital file, providing that file to the patron, and tracking the loan. As you think about systems that mimic these six steps, the kinds of architecture generally fall into four buckets. The first two are within an institution: an institution's own items with an institution's own patrons. The second two involve controlled digital lending on a collaborative scale—where the owning library is different from the patron's library. Let's take these in turn and see what the impact is on the six workflow steps.

CDL Model 1: Standalone CDL

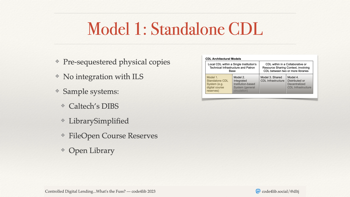

Presentation slide 11: Model 1– Standalone CDL

In this first case, there is a standalone CDL system. It isn't tied into the ILS to determine whether there is a physical copy. Instead, the physical copies are "pre-sequestered" — they are pulled out of the collection, digitized, and set aside. This is probably the simplest form of CDL, and it is something that might be found in a course reserves system, a remote storage environment, or special collections items. In the second step—the one where the system is estabilishing loan eligibility, we only need to see if the patron is allowed to access the item. The library has already determined that the physical item can be lent with CDL. In the third step—where we are ensuring the Own:Loan ratio is kept, the CDL system just needs to keep a counter of the number of digital copies of an item it can lend and the number that have been lent. We might be using NCIP to determine patron eligibility, or that might come as an attribute from a single sign-on system. So, yeah, the simplist. Some examples of this kind of model are Caltech's DIBS system, LibrarySimplified, FileOpen Course Reserves, and the Internet Archive's Open Library.

Presentation slide 11: Model 1– Standalone CDL

In this first case, there is a standalone CDL system. It isn't tied into the ILS to determine whether there is a physical copy. Instead, the physical copies are "pre-sequestered" — they are pulled out of the collection, digitized, and set aside. This is probably the simplest form of CDL, and it is something that might be found in a course reserves system, a remote storage environment, or special collections items. In the second step—the one where the system is estabilishing loan eligibility, we only need to see if the patron is allowed to access the item. The library has already determined that the physical item can be lent with CDL. In the third step—where we are ensuring the Own:Loan ratio is kept, the CDL system just needs to keep a counter of the number of digital copies of an item it can lend and the number that have been lent. We might be using NCIP to determine patron eligibility, or that might come as an attribute from a single sign-on system. So, yeah, the simplist. Some examples of this kind of model are Caltech's DIBS system, LibrarySimplified, FileOpen Course Reserves, and the Internet Archive's Open Library.

CDL Model 2: Institution-scoped Integrated System

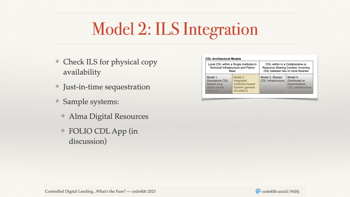

Presentation slide 12: Model 2– ILS integration

The second model is still within an institution, but in this case we're adding connections to the ILS. In the third step, we're going to look into the ILS to see if there is a physical copy available that can be digitally lent. If there is, we might print a paging slip to have the item pulled from the shelf or we mark an item in remote storage as unavailable. This probably involves checking out the item in the ILS so the normal unavailable ILS status appears. Once the system has verified that the physical item is no longer available, the request passes the Own:Loan ratio step. The physical item may need to be digitized or there might already be a digital file available. This architecture is probably using protocols like NCIP to interact with the ILS for placing holds, checking out items, and checking them back in. Examples of this kind of model out in the world is Ex Libris' Alma Digital Resources product; the FOLIO community is talking about developing a CDL app as well.

Presentation slide 12: Model 2– ILS integration

The second model is still within an institution, but in this case we're adding connections to the ILS. In the third step, we're going to look into the ILS to see if there is a physical copy available that can be digitally lent. If there is, we might print a paging slip to have the item pulled from the shelf or we mark an item in remote storage as unavailable. This probably involves checking out the item in the ILS so the normal unavailable ILS status appears. Once the system has verified that the physical item is no longer available, the request passes the Own:Loan ratio step. The physical item may need to be digitized or there might already be a digital file available. This architecture is probably using protocols like NCIP to interact with the ILS for placing holds, checking out items, and checking them back in. Examples of this kind of model out in the world is Ex Libris' Alma Digital Resources product; the FOLIO community is talking about developing a CDL app as well.

CDL Model 3: Consortium Shared Infrastructure

Presentation slide 13: Model 3– Consortium Shared Infrastructure

In the third and fourth models, we bring a consortium into the mix. In the third model, we look at the consortium's holdings as a shared pool of physical items. In the second step, the system needs to handle patrons from any library in the consortium as it is deciding on eligibility. In the third step, the system can look across all of the holdings of a consortium to match the loan of a digital item to a patron at library A with a sequestered physical item at library B. As you might imagine, we are increasing the complexity of the CDL system. Is there a shared inventory of physical holdings, or are availability lookups done against each library at request time? Are the digital files held centrally or do they remain at the owning library? How does a patron with credentials at library A get access to digital file at library B? This starts to look a lot like interlibrary loan, so what kind of hooks are needed into ILL management systems like ILLiad and Tipasa? In this space, Project ReShare's CDL offering is in development now and it leverages ReShare's Shared Inventory and Returnables apps.

Presentation slide 13: Model 3– Consortium Shared Infrastructure

In the third and fourth models, we bring a consortium into the mix. In the third model, we look at the consortium's holdings as a shared pool of physical items. In the second step, the system needs to handle patrons from any library in the consortium as it is deciding on eligibility. In the third step, the system can look across all of the holdings of a consortium to match the loan of a digital item to a patron at library A with a sequestered physical item at library B. As you might imagine, we are increasing the complexity of the CDL system. Is there a shared inventory of physical holdings, or are availability lookups done against each library at request time? Are the digital files held centrally or do they remain at the owning library? How does a patron with credentials at library A get access to digital file at library B? This starts to look a lot like interlibrary loan, so what kind of hooks are needed into ILL management systems like ILLiad and Tipasa? In this space, Project ReShare's CDL offering is in development now and it leverages ReShare's Shared Inventory and Returnables apps.

CDL Model 4: Decentralized CDL

Presentation slide 14: Model 4– Decentralized CDL

In the fourth model, we are well within the land of controlled digital lending as interlibrary loan. I've tried to get the acronym "CDILL" to stick to represent this kind of architecture, but so far have failed. In this architecture, there isn't a "CDL system" per se, but rather components at different libraries that are using well defined standards to pass messages about requests, availability, and loans. If you are familiar with the ISO 18626 standard for passing ILL requests between systems at different libraries, just think about those same pathways being used to pass a request to sequester and deliver a digital item from a supplying library to a requesting library. You might also consider a scenario where a request is made at one library, a physical copy is sequestered at a second library, and a third library delivers the digital file.

Presentation slide 14: Model 4– Decentralized CDL

In the fourth model, we are well within the land of controlled digital lending as interlibrary loan. I've tried to get the acronym "CDILL" to stick to represent this kind of architecture, but so far have failed. In this architecture, there isn't a "CDL system" per se, but rather components at different libraries that are using well defined standards to pass messages about requests, availability, and loans. If you are familiar with the ISO 18626 standard for passing ILL requests between systems at different libraries, just think about those same pathways being used to pass a request to sequester and deliver a digital item from a supplying library to a requesting library. You might also consider a scenario where a request is made at one library, a physical copy is sequestered at a second library, and a third library delivers the digital file.

Hachette/IA lawsuit

Presentation slide 15: Hachette versus Internet Archive

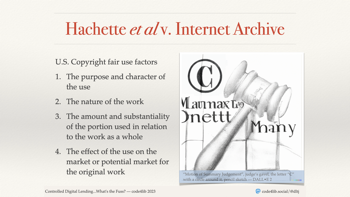

So that probably sounds like a lot of fun to us technologists, but why should we keep the fun to ourselves? Let's get the lawyers involved, too! As you might imagine, publishers are looking at CDL and saying "What? Wait!" The big four publishers—Hachette, HarperCollins, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House—sued the Internet Archive over its early-pandemic National Emergency Library, but the lawsuit has turned into an examination of the legal basis for Controlled Digital Lending. The Internet Archive asserts that CDL meets the criteria for fair use under United States law. As you might recall, the test for whether an activity is fair use has four factors:

Presentation slide 15: Hachette versus Internet Archive

So that probably sounds like a lot of fun to us technologists, but why should we keep the fun to ourselves? Let's get the lawyers involved, too! As you might imagine, publishers are looking at CDL and saying "What? Wait!" The big four publishers—Hachette, HarperCollins, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House—sued the Internet Archive over its early-pandemic National Emergency Library, but the lawsuit has turned into an examination of the legal basis for Controlled Digital Lending. The Internet Archive asserts that CDL meets the criteria for fair use under United States law. As you might recall, the test for whether an activity is fair use has four factors:

- The purpose and character of the use

- The nature of the work

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the work as a whole

- The effect of the use on the market or potential market for the original work

The Internet Archive asserts that CDL strongly favors the first and fourth factors and is neutral on the second and third. Needless to say, there are a lot of legal theories and precedents being staked out on both sides. This case was filed in June 2020 and is about to reach an interesting milestone. Both sides have filed a "motion for summary judgement" which is a lawyerly way of telling the judge that the facts of the case are so obvious that of course the court needs to side in their favor. That both sides have filed such a motion means that the facts may not be so obvious, but we will hear what the judge has to say about that on Monday afternoon. So keep your ears open for that, but it seems like this case may go through a years-long process before we get to any kind of ruling.

More about CDL

Presentation slide 16: For more information...

So I'm going to post these links to Slack on where to go to get more information. The first is the whitepaper on controlled digital lending of library books. It is a long and detailed exploration of CDL. The whitepaper was written by lawyers, so it has 166 footnotes, but it is an easy read. Second is the CDL Implementer's group. This is a mailing list and monthly webinar of libraries and service providers that want to implement CDL functionality. Third, if you can get enough of the law stuff, is to watch the documents coming out of the publisher's lawsuit; this is a link to CourtListener that mirrors documents that are behind the federal court system paywall . If you want to go all the way back to the beginning, then the place to start is Michelle Wu's 2011 paper for Law Library Journal, Building a Collaborative Digital Collection: A Necessary Evolution in Libraries, and you can find a copy in the Georgetown Law institutional repository.

Presentation slide 16: For more information...

So I'm going to post these links to Slack on where to go to get more information. The first is the whitepaper on controlled digital lending of library books. It is a long and detailed exploration of CDL. The whitepaper was written by lawyers, so it has 166 footnotes, but it is an easy read. Second is the CDL Implementer's group. This is a mailing list and monthly webinar of libraries and service providers that want to implement CDL functionality. Third, if you can get enough of the law stuff, is to watch the documents coming out of the publisher's lawsuit; this is a link to CourtListener that mirrors documents that are behind the federal court system paywall . If you want to go all the way back to the beginning, then the place to start is Michelle Wu's 2011 paper for Law Library Journal, Building a Collaborative Digital Collection: A Necessary Evolution in Libraries, and you can find a copy in the Georgetown Law institutional repository.

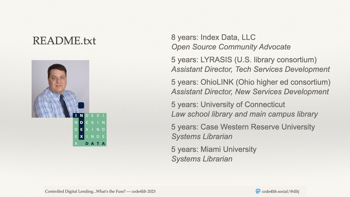

About the presenter and the presentation

Presentation slide 17: About the speaker

Presentation slide 17: About the speaker

Presentation slide 18: Closing information

Presentation slide 18: Closing information