OCLC Introduces "A Web Presence for Small Libraries"

On Sunday evening, the OCLC Innovation Lab held a public demonstration of a project with the working title, A Web Presence for Small Libraries It is a templated website that could serve as a library's barest bones presence on the web. The target audience is small and/or rural libraries that may not have the technological infrastructure -- human knowledge, equipment, and/or money -- to host their own web presence. If it comes to fruition, the basic service would give a library four pages on the web that can be customized by the library staff plus dynamic areas of content that would be generated by OCLC algorithms and optionally placed on each library's site. A more advanced version of the service could include a light-weight book inventory and circulation option.

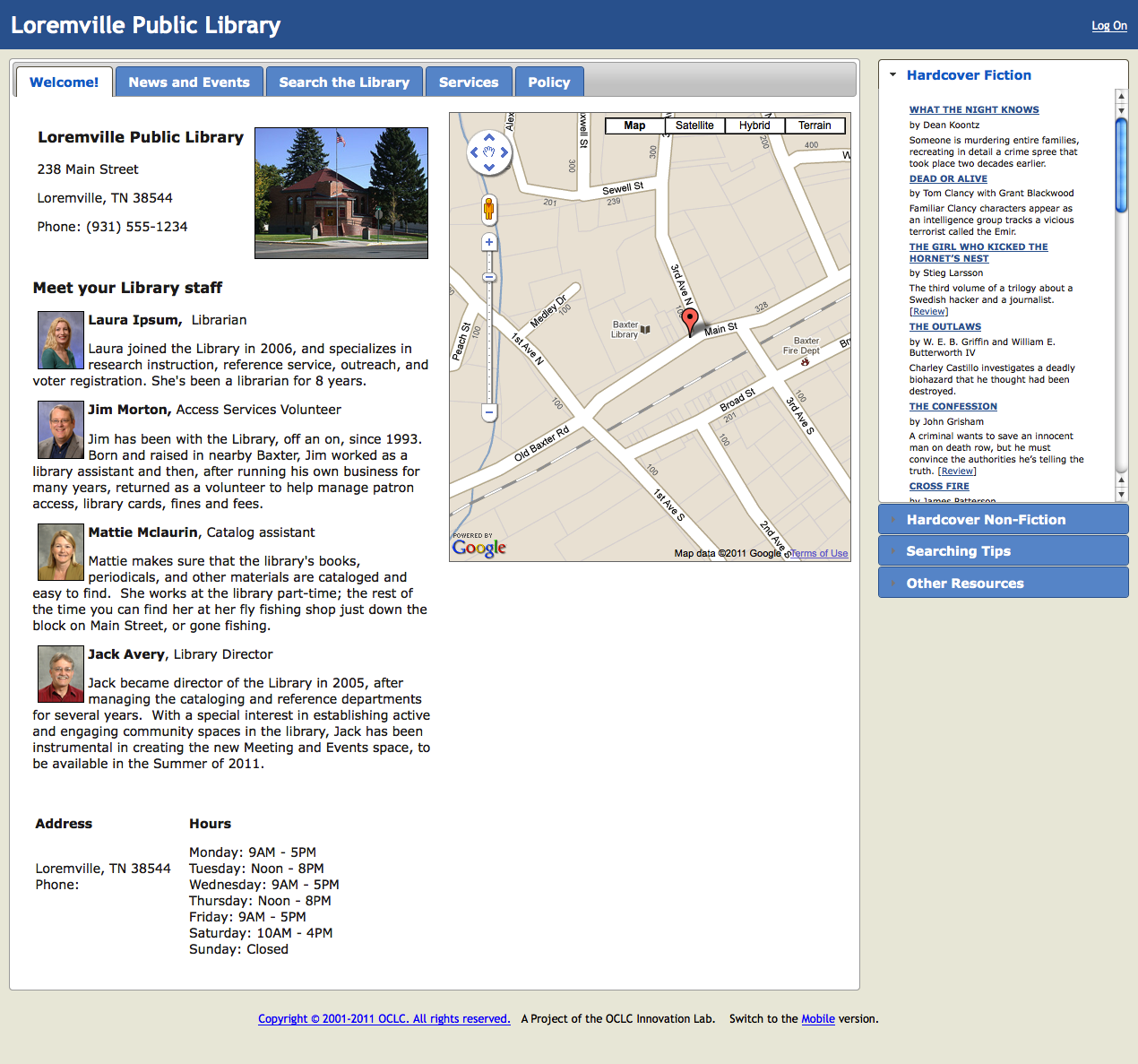

They created a sample library called Loremville, TN public library to demonstrate key aspects of the service. I did not ask them how long that particular example will be around, so you may follow that link at a later date and not find it.

This "Library Website in a Box" is a concept that has been around for many years, and the latest trigger to try something was a resolution from the last OCLC Members Council to make scaled-down versions of OCLC services for "small and rural libraries." The Innovation Lab group conducted some research about the existing state of public library web presences by sorting the IMLS-reported data from 2008 IMLS-reported data from 2008 by number of volumes held and number of library staff. They looked at the lowest quartile (roughly 20,000 volumes or less and staff size in the low single digits) and found that there was generally no web presence for these libraries. In the second quartile there were instances of library websites, but they did the library no credit (outdated, poorly constructed, incomplete information -- as was said at the meeting, these libraries had a presence on the web but probably shouldn't). Some had automation systems supplied by large groups, but others didn't have evidence of an automation system. So the project charter was to find an easy and inexpensive way for a library in these quartiles to create a desktop and mobile device web presence.

One of the unique aspects of the project development was to first set the approximate lower ($5/month) and upper ($40/month) price boundaries and find a way to provide the highest level of service possible at those price points. The Innovation Lab team tried techniques such as a farm of WordPress sites but found they couldn't make the revenue-versus-cost equation to work. In the end they constructed a custom database-driven content system in PHP. Institutional data is initially pulled from sources such as the WorldCat Registry, and there will be some process for a library to "claim" its site. There might also be a way for a library to create a site for itself if no registry data yet exists.

There are four levels of site authorization: public (unauthenticated) viewing, a registered patron, a staff member, and an administrator. Content from the pages are edited by the administrator at the subscribing library with a WYSIWYG ((What-You-See-Is-What-You-Get, meaning as you edit the document with styles like bolding, underlining, and bulleted lists, what you see in the editing interface is exactly how it will appear in the viewing interface.)) editor. There are content boxes for the library's location, staff/volunteers listing, events calendar and news, hours and phone number, policies, and service information. The library's address is fed into a Google Maps service to display a map of the area surrounding the library.

The dynamic parts of each library's website could have a list of books from various sources like the New York Times and Oprah's book group. The service also envisions offering a "default digital collection" using public domain works in text, PDF, and mobile reading device formats from sources such as Project Gutenberg and the Internet Archive.

The inventory and circulation module is simple and straight-forward. Each item has only eight full-text fields with the intention that the description will likely be done by a volunteer without professional library training. Cataloging can be done by typing in the information or scanning the ISBN with an app on a mobile device; item information is pulled from WorldCat if found. The cataloging application does not attach holdings to WorldCat, but the OCLC number is kept and might be used to facilitate offloading MARC records in cases where a library outgrows this simple circulation module to a more functional integrated library system. The circulation functions are check-in, check-out, renew, place hold and cancel hold. There are no financial functions in the system.

At these price levels, the system needs to be highly automated and self-supporting. The cost to OCLC of one call to a customer support phone number could easily run through all the revenue OCLC would receive from the subscribing library in a year. A widely adopted implementation at the targeted price points means that OCLC could dedicate one or two technical staff to support and upgrade the system in addition to the hardware and support service amortization.

One unresolved issue is domain names -- what is the URL that will be used for each library's site. OCLC is investigating options such as partnering with a domain registrar company (someone like GoDaddy), becoming a domain registrar themselves, or putting all the sites under one domain. The economics of each of these options will be a factor. The sometimes cumbersome aspects of migrating domain names from one service to another may make that activity cost-prohibitive as well.

Mike Teets noted that this was at a "project" stage, not a "product" stage. My paraphrasing of what this distinction means is that the technology to create a product is largely done, but the decisions on the final formative pieces of the technology and the surrounding support infrastructure -- is not yet done (and might never be done). There isn't even a formal name for it yet; it is being called "A Web Presence for Small Libraries." One desired additional feature is to add e-mail boxes for library staff/functions to the site. Those in the room, including me but more importantly others who are more closely aligned with the target "small and rural" public library population, were pretty excited about it and wanting to talk further about if what we saw could be made a reality.

Personal Impressions

Like others in the room, I came away impressed by the project demonstration. It is definitely fits the bill as a basic library website and even a starter inventory and circulation management system. I see that libraries could start with something like this for the cost of a couple of books added to the collection (roughly estimated at $60/year). At this price level, OCLC thinks they could sustain the costs of operations plus have some left over for investment in incremental improvements. I also think that because a library would pay a minimal fee for it, they would feel a tangible sense of ownership over the site and would keep them up-to-date. From this a library could "graduate" to another service -- their own Drupal or WordPress site, to a shared ILS or Webscale Management Services.

The content areas seemed the most appropriate for the target audience. The web page design is modern, and I could see options for future enhancements as time and revenue permit such as providing limited options to personalize the template (change colors, adding picture -- or adding links to pictures that might be stored on services such as Flickr).

One attendee at the session suggested that rather than OCLC prepopulating a digital content library of all public domain content that the set be limited to those that are most downloaded so as not to overwhelm the user with a lot of unused (and/or unusable) digital content. That sounds like a good suggestion to me.

OCLC Staff are looking for feedback on this project. They say that the system is "production ready" with all the software controls and data recovery features of OCLC behind it. What they think is missing is community support to have local engagement with the targeted libraries to show them what is possible. That is an area where OCLC needs help. (I can only imagine the shocked silence of a volunteer at a small library to get a call from OCLC -- if they even knew what OCLC was -- with an offer to create a website for the library. "Only $5/month...sign up now and we'll throw in a second one for free!") There is an e-mail address -- innovation@oclc.org -- that goes to all the OCLC Innovation Lab members, and a WebJunction group

About the Innovation Lab

The OCLC Innovation Lab is a new unit headed up by Mike Teets. The group has four full-time people (Mike plus Tip House, Rob Koopman and Willie Neumann) and leverage staff from other parts of OCLC to work on projects. (Willie performed the demonstration at Midwinter.) Their charge is to be a quick and nimble team to go after problems of a business unit of the cooperative or something from OCLC as a whole that wants done but hasn't made progress. They like to use this quickness as a positive attribute to intentionally limit the scope of projects. Since its formation in April 2010 it has come up with roughly one new thing a quarter, including the WorldCat Mobile interface (build in 22 days, Mike noted) and the Ask4Stuff Twitter service.

For this project, the Innovation Lab sought out cooperation from OCLC staff to build prototypes and components of the service in their spare time. Each Monday the self-selected group would get together to show what had been built and discuss ways to move the project forward in the following week. In this way they rapidly iterated over ideas to come up with what was ultimately proposed.