Refactoring DLTJ, Winter 2021 Part 1: Picking up Obsidian

As 2021 comes to a close, I've been thinking about this blog and my own "personal knowledge management" tools. It is time for some upgrades to both. The next few posts will be about the changes I'm making over this winter break. Right now I think the updating will look something like this:

- Ramp up automation for adding reading sources to Obsidian (this post)

- Refactor the process of building this static website on AWS

- Recreate the ability for readers to get updates by email

- Turn the old DLTJ "Thursday Threads" concept into a newsletter

I'll go back and link the bullet points above when (if?) I create the corresponding blog posts.

I've been using Obsidian for about six months as a place to note and link ideas on stuff I'm reading and watching. In case you haven't run across it yet, Obsidian is a personal wiki of sorts. It is software that sits atop a folder of Markdown files to provide indexing as well as inter-page linking and graph views of the folder's contents. Most people use it to build up their own personal knowledge management (PKM) database. You can make notes for the sources you are reading, then build knowledge by linking sources together using keywords and adding commentary at the intersection of related ideas.

Before Obsidian, I was using the Pinboard service to store bookmarks of interesting sources and using the paid subscription search engine and my own memory to find stuff. I've found that this setup works okay for retrieval—I can usually find things that I know I've read about before—but doesn't do so well for making new connections or creating new knowledge. The Thursday Threads series on this blog years ago was, in part, a way to find those connections and explore them a little bit in writing. I'm expecting Obsidian to help improve this area.

The start of the knowledge curation process is creating pages in Obsidian for the important/useful things I'm reading—each of these is a "source". I like the idea of having a bookmark service as the start of the queue of sources feeding into the PKM; It is a universal tool that is available from a wide variety of entry points. In my desktop browser, I use the Pinboard Bookmarklet to add new sources. On iOS, I use the Pins app on the share sheet to add things. The Pins app works not only in Safari but also in other places like the New York Times and Twitter apps.

To get sources from Pinboard into my Obsidian PKM database, I wrote a Python script that uses the Pinboard API to copy bookmarks into an intermediate SQLite3 database, and then every morning creates a page in the Obsidian database for each new source. Please note that this Python script is quite the mess; it started simple but has had functionality grafted into it a dozen times now, and it is in need of a serious rewrite. For better or for worse, it is out there for others to inspect and get ideas from.

For the sources I add to my PKM, I'm also concerned about link rot (web resources that go missing) and content drift (resources that change in between the time you first read them and when you or someone else goes back to them). To combat this, the script sends an API call to the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine to save the contents of a web page. I'm able to retrieve the Wayback archive URL and save that in the SQLite3 database. This is useful not only for my own reference but also for when I publish blog posts. You've probably noticed the link symbol to the right of hyperlinks on this page; those are robust links in practice—it opens a drop-down menu that takes you to the archived version of the linked webpage. (The robust links concept probably deserves a blog post all its own.)

Another side effect that I wrote into the script was to post my public bookmarks to Twitter and Mastodon. (For a long time I used the Buffer service to do the same thing, but over the years I had less and less control over how and when Buffer posted links.) I hope that posting these sources publicly will generate more conversation on the topic that I can add to my notes.

Each bookmark on the Pinboard service has a field for a description and a field for tags, and those are okay as far as they go. For some sources, though, I found myself wanting to comment in a more structure way, and so I reintroduced myself to the hypothesis.is service. Hypothes.is allows you to comment on any web page or PDF, and share those comments with others. More importantly, Hypothes.is lets you comment on selected portions of a document, and stores enough context to find that same location even when the underlying document changes. Hypothes.is as a service is embedding itself into learning management systems as a way for students to collaboratively critique content on the internet, but it is also useful to average folks. My Python script uses the Hypothes.is API to read my stored annotations, then gathers all of the annotations for one source onto its own page in the PKM database.

So that is what I've been running with for a number of months. This week I've been adding some enhancements to the Python script. The first change was to make each Pinboard bookmark its own page in the PKM database. When I started out months ago, I thought my "Sources" area of my Obsidian PKM would get polluted with small, stub pages because the only content was a link to the source and the topical keywords. So initially the script just added the links to the sources on a "daily notes" page. I found this ended up polluting the PKM's knowledge graph, though, because unrelated daily note pages would be linked through topical keywords from sources that were only related because I happened to read them on the same day.

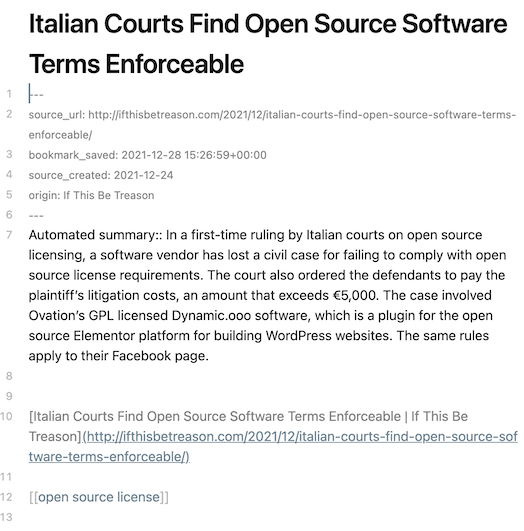

Second, to add more "heft" to these source pages in the PKM, the script now adds a summary paragraph. It does this by scraping the main content of the webpage (using trafilatura) and picking the most important sentences (using the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) and the technique described by Ekta Shah). I'm expecting that no matter what I've written about the source or the keywords I've assigned to the source, these summaries will provide another valuable way to retrieve pages and concepts. (The NLTK toolkit has other text processing features—entity recognition, sentiment analysis, etc.—and I might explore additional information to the Obsidian PKM pages with those tools.)

Third, I started adding more metadata to the top of each PKM page. I'm expecting this metadata will be useful in the future, especially for functionality like reminding myself of saved sources after six months or a year.

The result of all of this work is an Obsidian page that looks like this:

I think I'm done for now with this Python script that injects new sources into my Obsidian PKM database. The next big thing is some kind of topical keyword management...a personal ontology service of sorts. (If you know of any sofware like that—particularly something that works with Obsidian—please let me know.) Eventually, I'd like to add a mechanism that pulls annotated text from Kindle books as new sources. I'd also like to find a way to get a list of podcast episodes that I've listened to and add those as well. But for now...until that rewrite...good enough.