On the Pitfalls of Social Media: Learning from Clinical Reader

As a youth I remember intently studying the troubles of others -- what they did when they got into trouble and how they got out of it. If the saying "You Learn From Your Mistakes" was so true, I wanted to be able to learn from the mistakes of others. I don't do that as much anymore -- probably because I have more than enough of my own mistakes now to learn from -- but every once in a while a situation comes up where this urge strikes. The case of Clinical Reader resurfaced that youthful urge.

I started the previous post thinking I would quickly get to the end and summarize some observations and recommendations for libraries considering their official entrance into Twitter and other social media spaces. As I kept saving the draft of the post in my blog software each evening, it kept getting longer and longer as the story of Clinical Reader got stranger and stranger. (At one point it became a Herculean effort just to keep up with the Twitter account changes to make sure the links pointed to the right place. There are probably some that are still wrong.)

So I moved these observations and recommendations to this new posting, and at the same time changed the tone of the writing from a formal case study to a more informal blog posting. While this posting is meant to be read and appreciated in isolation from the description of the troubles of Clinical Reader in the previous posting, you may want to skim through it to get an appreciation of how the mistakes that were made were seen by me and others. I will repeat the backstory from the first post, however, to give context for what follows.

Repeat of the Backstory

Clinical Reader started operations earlier this year as point of aggregation for medical information. The service's about page describes their "beginnings" this way:

Clinical Reader was brought to life in 2009 by a junior doctor and a small group of forward thinking young tech programmers spread across London and Toronto. The conceptualized idea was to manage clinical information overload and deliver relevant news from an authoritative source on a daily basis.

On the technical side, it is a website that syndicates content via RSS/Atom from various journals, news sources, blogs, and social media outlets. There is the appearance of editorial decision making in the form of an "Editor's Choice" list (with no apparent description of how or why something makes this list), but mostly it seems to be a way to hide the complexity of syndicated content readers from those in the medical profession who could care less about such complexity.

Observations and Recommendations

Given Enough Eyeballs, All Falsehoods Are Shallow.

Author and software developer Eric Raymond formulated Linus' Law to describe the software development philosophy of the creator of the Linux kernel, Linus Torvalds: "Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow." The statement stems from belief and observation that given a large enough group of software developers and software testers, "almost every problem will be characterized quickly and the fix obvious to someone." ((The Cathedral and the Bazaar by Eric Steven Raymond, version 3.0 (dated 2-Aug-2002), chapter 4.)) I propose a generalization of Linus' Law. Call it "Jester's Law", if you will: "Given Enough Eyeballs, All Falsehoods Are Shallow"

The original discovery by Nicole Dettmar of the questionable endorsement is a prime example of this Jester's Law. Hundreds if not thousands of people that used the Clinical Reader website prior to Nicole's blog post on July 13th probably thought the endorsement by the National Library of Medicine was real. It was Nicole, however, that knew better, and she had a platform with which to call attention to the issue. There are other examples of Jester's Law -- the copying of the "tangled strings" graphic from the Feedstitch service (later refuted by the Feedstitch developers), and changing inflammatory wording in their newsletter (the previous wording was found in the Google search engine cache).

If you have something to say in the social media space (or anywhere else, for that matter), be as truthful as you can. The opportunities for others to find your falsehoods grows dramatically in social media, and the same social media can be used to spread word of those falsehoods.

Mistakes Happen, You Can't Hide Them.

When you make an error, or -- heaven forbid -- your lie is caught, you simply can't delete the incriminating evidence. Digital content quickly takes on a life of its own as it is copied from web server to browser histories to web search caching engines and syndication services. Nicole copied some of her and ClinicalReader's tweets to QuoteURL (a service that archives Twitter conversations). Luke Rosenberger copies the entire history of ClinicalReader's tweets to the Iterasi web page archiving service. Allan Marks, a co-founder of Clinical Reader, renames the services Twitter account and deletes the controversial tweets, but they are still out there. (These blog posts, in their own way, will preserve them as well.) A copy of the Clinical Reader newsletter was in Google's search engine cache -- the version without the quick change made by a Clinical Reader staff member.

Mistakes Happen, Own Up To Them.

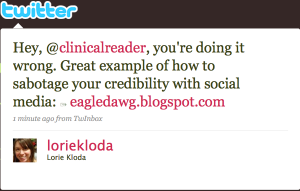

Related to the previous observation is that you have to acknowledge your mistakes. It took too long for someone from Clinical Reader to acknowledge the issues and take steps to fix them. (Some would probably argue that at the point this posting is published, Clinical Reader still hasn't done that.)

There are probably lessons to be learned here that can be taught by the world of public relations and "damage control," and likely better descriptions of ways make sincere and decisive statements that show you are taking the issues seriously and fixing them. Again, as a counter example, what Allan Marks of Clinical Reader did has not -- to this point -- instilled the confidence of the library community he was courting as a way to spread information about his service.

140 Characters Is Too Short To Say Important Things.

Particularly things that are intended to save the reputation of your organization. There comes a point when you need to address the issues at length and point people in the Twitter universe to that. Nicole was trying to help Clinical Reader in this respect by seeking and gaining permission for her to repost Allan's private e-mail apology. Such long-form messages should be posted on your website, though, so people know it comes from you in some official form.

A corollary to this observation is that, even with just 140 characters, spelling and grammar count towards (or detract from) credibility. More than one person had access to the Clinical Reader account, and while this was admitted to in the course of the issue one could also tell by the bad spelling and grammar of at least one person.

Establish Ground Rules for Shared Accounts.

Clinical Reader admitted that there was more than one person using the "ClinicalReader" Twitter account. Allan Marks was wise to let people know when it was him posting messages with shared account. Even after Allan stepped up to address the issues, though, there seemed to be other people posting messages that aggravated the issue. (I would also fault Allan for never really coming clean to say who he was despite repeated requests for him to do so.)

Don't Simply Abandon Your Online Presence(s)

This advice applies to more than just social media accounts related to your organization. It also applies to things like domain name registrations. It is a well-known trick of search engine optimization "black hats" ((A "black hat" is someone who uses nefarious means to achieve a goal. See the definition in Wikipedia for more information.)) to attempt to reregister accounts/domains that have expired or been abandoned. Allan's attempts to dodge the issues of the week with Clinical Reader by renaming the service account have cause considerable confusion and likely alienation of anyone who was previously loyal to the service.

Other Commentary

Commentary on the Clinical Reader has been coming in from various corners of the web, and interestingly (I think) the commentary has been coming in from people outside the medical librarian community. This, too, is an effect of the nearly frictionless nature of social media. For instance, Jill Hurst-Wahl has a list of do's and don't for her clients. The principals behind Clinical Reader acknowledge Jill's recommendations, but the community has yet to see them in practice. There are also postings in FriendFeed by Rachel Walden and Steve Incandenza with further observations. Lastly, Nicole Dettmar, as the person initially in the center of the controversy, notes some issues (and, if your learning from this example, some recommendations) with Clinical Reader's response in the form of an open letter to its management.

Conclusion

As I stated in the introduction to the previous post, there is a pace of information flow in the social media space that is unlike anything else in the physical world, and a minor incident -- be it an ill-advised policy decision or an unfortunate slip of the tongue -- can quickly spiral out of your control. That doesn't mean that you don't meet your organization's users there. It does mean, though, that you do so in a thoughtful manner. Some common sense -- applicable to any form of media -- plus some time familiarizing yourself with the ebbs and flows of the social media landscape will serve your organization well.

The text was modified to remove a link to http://twitter.com/amarks7/status/2619628917 on February 11th, 2011.

The text was modified to remove a link to http://twitter.com/amarks7/status/2689499674 on February 11th, 2011.

The text was modified to remove a link to http://www.clinicalreader.com/ on February 12th, 2011.

The text was modified to remove a link to http://www.pointlesscorp.com/imitation-is-the-sincerest-form-of-theft/ on November 16th, 2012.