On the Internet, How Do You Know If You Are Talking to a Dog?

Image from The Cartoon Bank

The famous 1993 cartoon from The New Yorker has the caption “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” The question at the moment is: when you're on the internet, how do you know you are not talking to a dog? When you ask to connect to a remote service, you expect to connect to that remote service. You probably don't even think about the possibility that "myspace.com" might not be "myspace.com". But what if you couldn't rely on that? How about "mybank.com"? Believe it or not, you may exist in such a world today. Last week, US-CERT issued a "Vulnerability Note" on Multiple DNS implementations vulnerable to cache poisoning. What does that mean? Read on...

DNS: The Internet's Addressbook

Your computer (or, in some special cases such as a home network setup, "your entire network" ((This happens with a technique called "Network Address Translation" or NAT. NAT was created to conserve the internet address space (among other reasons) by putting multiple computers behind a device that makes all of the computers look like one machine to the outside world. If you connect to the rest of the world via a small hub, you're probably using NAT. If the IP address of your computer starts with "10" or "192.168" you are definitely using NAT.))) is uniquely defined on the internet by an "IP address". It is a series of four numbers separated by a period; something like "216.178.38.116". Every computer on the network has one. The issue is that these numbers are not as easy to remember as names like "myspace.com". Enter DNS...

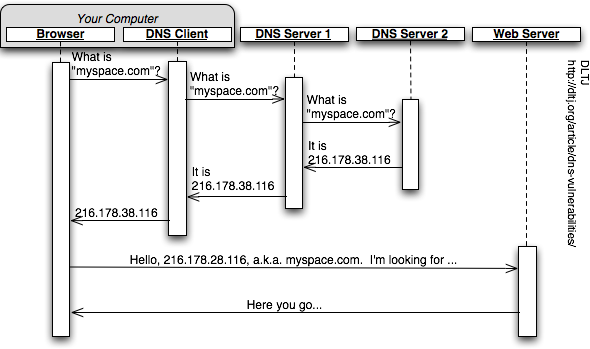

It is the Domain Name System, or DNS, that translates an easily recognizable name to an IP address. DNS is a distributed database of names-to-numbers (and numbers-to-names and all sorts of other mappings). A network machine -- say, your desktop computer -- is running a program (a web browser) that needs to connect to a server. It relies on a DNS client to perform the name-to-number mapping. This figure shows a simplified relationship between all of the parts.

On your computer, the web browser makes a request with the local DNS client to one of the DNS servers it knows. (You'll see this DNS service listed if you look at the network properties on your computer.) DNS servers can, and typically do, remember the answers to recently asked questions from other DNS clients (a feature called "caching"); if the DNS server can answer the question from its cache, it will. If not, one of two things can happen: 1) DNS Server 1 can send a message back saying it doesn't know but suggest where it might go to find an answer; or 2) attempt to find the answer itself and send it back to the DNS client. The latter is what is pictured above and is called "recursive name resolution". DNS Server 1 can also cache the information so as to answer a subsequent question for the same information without having to go out and ask another DNS server for it. ((The amount of time a caching DNS server can hold onto information on behalf of an "authoritative" DNS server is specified as part of the DNS protocol, but such consideration is outside the scope of what is being talked about here.))

When DNS Goes Bad

So what is the problem? The United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) describes it this way:

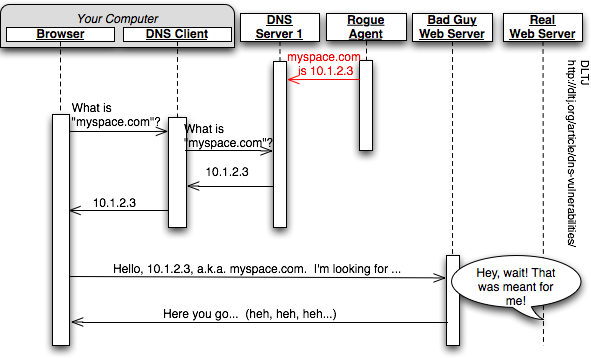

An attacker with the ability to conduct a successful cache poisoning attack can cause a nameserver's clients to contact the incorrect, and possibly malicious, hosts for particular services. Consequently, web traffic, email, and other important network data can be redirected to systems under the attacker's control.

In other words, some rogue agent out on the net tries to inject bad information into a DNS cache by sending specially constructed answers to questions that the caching DNS server never asked. That looks something like this.

As the US-CERT advisory points out, this is a bad thing. Many internet services rely on the fact that when they ask to connect to a host with a specified name that they will in fact be talking to a host with that name. You want to know that you are sending and receiving e-mail from the servers you expect and that the websites you get information from are the true, correct servers. DNS cache poisoning effectively hides this because the address bar in the browser looks correct.

Beyond Phishing

Note that this scheme is different from the "phishing" technique. In that technique, you might be ask to go to a URL like http://badguys.crimesyndication.org/banking.yourbank.com/, which would look and behave like the "banking.yourbank.com" site that you know, but it is really a website on "badguys.crimesyndication.org" that is simply made to look like your online banking site. Careful inspection of the URL and the hints supplied by the browser about the security certificate would show that you are connecting to the wrong place. The "DNS Poisoning" vulnerability is much worse because your computer was fooled into connecting to the wrong site and is passing that tomfoolery back to you.

One Possible Workaround, One Possible Problem

One of the possible workarounds is to configure your computer to use a DNS server that is not vulnerable to the problem of DNS cache poisoning. One such service is called OpenDNS, and they made quite a big point about not being vulnerable to this problem. At a very basic level, you use OpenDNS by setting your DNS servers to 208.67.222.222 and 208.67.220.220. Of course, they also offer more services layered on top of the basic name-to-address resolution service.

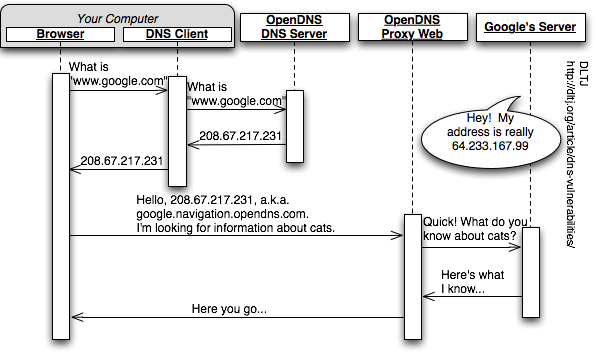

However, in the course of writing this posting, I discovered that OpenDNS itself is engaging in something moderately equivalent to DNS cache poisoning itself, and it is doing it with the address of the most popular website: www.google.com. The problem seems to stem from issues that OpenDNS users were having with hidden software installed on Dell machines as a result of a Dell/Google agreement. David Ulevitch, Founder and CEO of OpenDNS, posted about the impact of Dell/Google's actions and OpenDNS's response on the OpenDNS blog last year.

About a year ago Google and Dell announced a partnership to include the Google Toolbar on new Dell computers. At the same time, Google was trying to convince the Department of Justice that changing the default search engine in the (then) new IE7 was too difficult (when in reality it’s really simple). Installing the toolbar meant that users would have Google as their default search engine in IE7. It also meant that Dell and Google would share some of the revenue from the advertising clicks that resulted from these installations, much like The Mozilla Foundation does with its Firefox browser. ...

The solution to this problem was to route Google requests through a machine we run to check if the request is a typo or one of your shortcuts. If it is a typo or shortcut then we do what we always do, just fix the typo or launch your shortcut and send you off on your way. If it’s not one of those two things, we pass it on to Google for them to give you search results. This solution provides the best of both worlds: OpenDNS users get back the features that they love and Google continues to operate without problems.

This is what it looks like in a picture:

Danny Sullivan of Search Engine Land has a more in-depth analysis of Google's and Dell's actions. David offers a defense of OpenDNS's response in a comments on a post to Slashdot (this is the sharpest and most poignant). If offering OpenDNS as a fix for DNS cache poisoning is two steps forward, then OpenDNS's response to the Dell/Google action is, at best, one step back. I would prefer that Dell not automatically install functionality like this on my PC. I would also strongly prefer that DNS resolvers not try to be too cute. Fortunately, it is possible to turn off this behavior in OpenDNS, which I prefer to do. But, all told, this is just one more lesson about how important the Domain Name Services is to the fundamental operation of the internet, and how easy it is to take for granted.

Updates

18-Jul-2008: I exchanged e-mail with David Ulevitch, Founder and CEO of OpenDNS, that focused on the latter part this posting. He noted that "everything in our service, including the Google proxy, is an option that can be enabled or disabled in a (free, of course) user account." I implied that by linking to Ben Lowery's posting with instructions on "flipping the 'Enable OpenDNS proxy' toggle". So I wanted to explicitly call that out. David also pointed out OpenDNS is working with Google to create favorable peering arrangements at their distributed sites; doing so is decreasing the latency introduced by the proxy.

Also, there is a C|Net news article talking about how this broad, deep, and important problem was discovered and incrementally disclosed. It is a very interesting read for those who like to know about how internet security happens.

The text was modified to update a link from http://www.cartoonbank.com/item/22230 to https://www.condenaststore.com/-sp/On-the-Internet-nobody-knows-you-re-a-dog-New-Yorker-Cartoon-Prints_i8562841_.htm on November 8th, 2012.

The text was modified to update a link from http://www.us-cert.gov/aboutus.html to http://www.us-cert.gov/about-us on August 22nd, 2013.