The Complex World of the Textbook

Who knew the college textbook marketplace could be so complex? The agents in this ecosystem and their interests are so intertwined that as a whole it poses a massive amount of inertia for those who attempt to change the marketplace. I've been involved for about a year with an effort to change the textbook ecosystem for Ohio college students, and I am amazed at the complexity with each new layer of the onion that is peeled back. I thought it worthwhile to document my findings here and ask what insights others have.

The Big Picture

In July 2005, the United States Government Accountability Office published a report called College Textbooks: Enhanced Offerings Appear to Drive Recent Price Increases that documents in great detail the complexity of the textbook ecosystem.

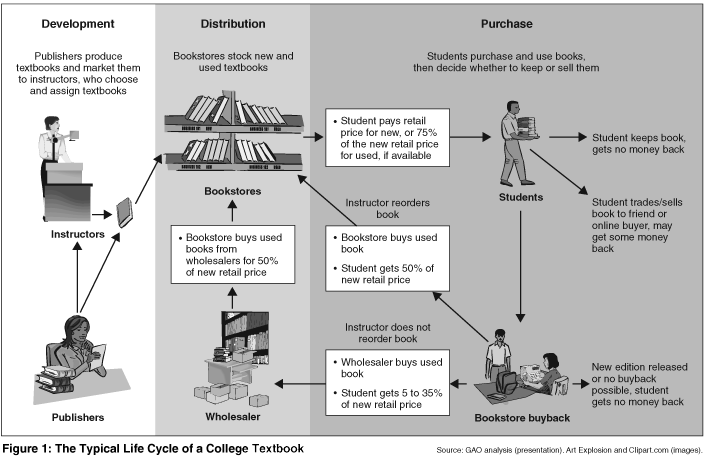

Figure 1 from page 5 of the report graphically depicts the life cycle of the college textbook along with the players in its ecosystem: publishers, instructors, bookstores, students, and used textbook wholesalers. The short version is this: Publishers create a textbook. Instructors tell Bookstores the textbooks they want to use for a course. Bookstores estimate the number of copies needed and buy stock from Used Textbook Wholesalers and Publishers. Students purchase the textbook from the Bookstore, and sometimes sell the textbook back to the Bookstore at the end of the term.

The Effect of Used Textbooks

There are, of course, many variables in this ecosystem. Used textbooks are highly sought by both the Bookstores and the Students. For Students, the used textbook is sold at a lower cost than the new version -- typically about 75% of the new textbook cost. For Bookstores, the sale of a used textbook is a higher margin sale -- averaging 33% versus the 23% margin for new textbook sales. ((The numbers are from page 13 of the GAO report.)) There are also actions that Bookstores can take to improve their margin. If the Bookstore knows that the Instructor will use the book again, it will buy back and warehouse more of that particular book from students at the end of the term. More used books held over by the Bookstore from term to term means the Bookstore does not need to buy and pay for the shipping of as many textbooks to meet student needs for the following term. The Bookstore may even offer higher prices to students who sell back these desired books. On the other hand, the Bookstore will offer lower prices for books that are not desired as much. A Bookstore may even refuse to buy back a current edition of a textbook when it knows a new edition is coming from the Publisher for the next term and the Instructor has requested the new edition.

So Bookstores try hard to get next term's textbook selections from Instructors before the current term ends. With that information the bookstore manager can make better guesses and assume less risk in buying back books that the Bookstore won't use. In the end, the Used Textbook Wholesaler is an agent that the Bookstore can use to attempt to smooth out the ripples between used textbooks on-hand and the demands for the new term. And as a last resort, since the margins are lower, it will stock new textbooks from the publisher. Between the actions of the Bookstore and the Used Textbook Wholesaler along with cooperation from Instructors, the used textbook market has become a very efficient part of the textbook ecosystem.

Publishers, on the other hand, probably don't like this increased efficiency in the used textbook market. A publisher makes no money on a used textbook sale, so it typically had two options: 1) raise the new textbook price to spread the fixed capital costs of creating a new textbook among fewer purchases; and/or 2) employ strategies to force Students to purchase more new textbooks. The former is a matter of simple economics; Publishers spend upwards of $1 million dollars to create the book and the accompanying materials ((See What Affects a Textbook's Price? on the Association of American Publishers' advocacy site "www.textbookfacts.org". Retrieved 3-Jul-2008)) and those costs must be made up somehow. The latter occurs by publishing new editions more frequently and/or through "bundling" (forcing students to buy the textbook by combining it with one-time-use consumables like workbooks or term-limited website passwords). [Update 20080710T0954 : Publishers have another way of restricting the used textbook market: custom publishing. This is discussed in an article in the Wall Street Journal.]

The Digital Option

There is a third option now: use digital delivery to eliminate the Bookstore, its markup and its used textbook market. By dealing directly with Students, the Publisher could remove the influence of the Bookstore and the Used Textbook Wholesaler from the ecosystem; as a consequence it can lower the price and increase its own margin. The Publishers also gain an advantage by removing the used textbook market; the Student's username/password to the digital editions hosted on the publisher's website expire after a set period of time (typically six months to a year). Expired username/passwords are worthless, so the secondary used market dries up. (There is typically also contract language that the user accepts during the purchase process that says the student will not share or resell access to the publisher's content.) No secondary market means that Publishers are assured of more sales to Students over the Bookstore-mediated market; as a consequence, the Publisher can spread their fixed capital costs over more unit sales, thereby lowering the per-unit cost.

Each of the major publishers has their own e-commerce site for digital textbook delivery, but the Publishers thought this was such a good idea (or at least thought it was a good idea to eliminate confusion on where to go to get an e-textbook) that they came together and formed a company called CourseSmart as a one-stop shop for students purchasing textbooks. ((CourseSmart exists for other reasons, as well. For instance, the task of getting sample physical textbooks to instructors that may adopt them is expensive to publishers in labor and shipping expenses. Digital delivery of the entire content of the textbook to instructors via a website is more cost effective. The sample copies also tend to end up in the used book market at some point, at which point is a completely lost sale for Publishers.)) The Bookstores, understandably, are not pleased with the creation of CourseSmart and its trade organization, NACS, is reviewing the arrangement through the lens of U.S. antitrust laws. The Bookstore is not out of the equation entirely, though.

The Bookstore's Response

Call it a variation on the Publisher's new digital delivery option: wholesaler-supplied e-textbooks. One of the largest Used Textbook Wholesalers, MBS, has their own multi-publisher e-textbook platform called Universal Digital Textbooks. It is not an e-commerce site -- one must purchase the access codes for the e-textbooks through a Bookstore -- but once one has access it is functionally equivalent to the CourseSmart site. It also happens that MBS and one of the largest college bookstore service providers, Barnes and Noble College Stores, share a common fiscal beneficiary, Leonard Riggio. This combined Bookstore/Used-Textbook-Wholesaler operation ((From a B&N

Barnes & Noble.com purchases new and used textbooks directly from MBS, a corporation majority-owned by Leonard Riggio.... In fiscal 2006, MBS began selling used books as part of the Barnes & Noble.com dealer network.... In addition, Barnes & Noble.com maintains a link on its website which is hosted by MBS and through which Barnes & Noble.com customers are able to sell used books directly to MBS.

The filing has descriptions of other relationships with Leonard Riggio and these various enterprises.)) has a deep interest in not being removed from the textbook ecosystem. The other major college bookstore management company, Follett, is following a similar path by recently purchasing another e-textbook operation called CafeScribe. (And if you think the matrix of players isn't complicated enough, know that Publisher-owned CourseSmart has now partnered with Nebraska Book Company, yet another college bookstore management company and Used Textbook Wholesaler, as a bookstore distribution channel for CourseSmart content.)

The Bookstore is also more than just a retailer of textbooks (electronic or not). It is also a service center for the purchase of textbooks. For instance, many bookstores will do the collection of required textbooks for Students and have the package ready for students to walk in and pay for. Bookstores are also agents for those receiving various scholarships (e.g. athletic and others) that include a textbook benefit provision. The Bookstore's accounting mechanism ensures that designated scholarship funds are spent only on textbooks. There is not a national database of such scholarship recipients that a site like CourseSmart could use to provide an equivalent service -- it is typically strictly a local endeavor. I've also heard in one anecdotal statement that Bookstores carry the debt of the sale of the textbooks to some scholarship recipients until the end of the term in accordance with the policies of the scholarship-granting agency. That may not be a service that a low-margin, online retail business model can offer. Perhaps this is the reason that Publishers seem to be unwilling to cut the Bookstores and the Used Book Wholesalers out of the digital market completely. After all, the Publishers have a choice as to whom they will give the digital version of their content; the Publishers could choose not to give the digital version to the MBS and Follett for their delivery systems. The reasons why Publishers would seemingly sacrifice margin to these alternate digital delivery systems is one of my unresolved questions.

And the Students? An Untested Analogy...

Students are reacting to increases in textbook prices in a way that is strikingly similar to that of the music recording industry versus listeners. The unit prices of the product have gone up (CDs / textbooks) while the introduction of ways to sell used items (CD exchange stores / textbook buybacks) result in a drop of first-copy sales. Digital delivery enters the landscape (via record company websites, iTunes and Amazon / publisher websites and bookstore/wholesaler websites), and the price drops a bit. (As we run our pilots, part of the equation is to seek a significant discount for digital delivery over the price of a new physical textbook.) Digital Rights Management is in the equation on both sides, with (in my opinion) only modest success. There are even reports of students engaging in digital piracy via Bittorrent with publishers clamoring to get the content removed and perpetrators standing behind a statement of “civil disobedience” against “the monopolistic business practices” of textbook publishers.

One clear difference is the time-sensitized nature: the CD tracks you buy from iTunes or Amazon don't expire while the business models of the online textbook distributors clearly involve disabling access to the content after a set period of time. (This business model is more like "digital rental" than digital ownership.) It is also true that the student's decision to buy is not without influence (the instructor determines the required textbook) or of a more life-altering nature (having and using the textbook would likely lead to a better grade, which is to say nothing of the likelihood of increased retention of the topic's concepts). I haven't thought completely through the analogy (hence the "untested" qualifier), but even with these differences it seems to hold together well.

Looking for a Path out of this Mess

I think it would be safe to say that no one is terribly happy with the status quo -- if there is such a thing as a steady-state with all of the pieces of the ecosystem changing so quickly. In addition to efforts in the Ohio legislature to get a handle on this, the federal reauthorization of the Higher Education Act contains provisions related to the disclosure of data in the textbook ecosystem. It would certainly have an impact on quality and quantity of information about the various flows of data in the ecosystem. The result will be a shifting of players and price in the marketplace, but I'm not convinced this leads to a more fundamentally ecosystem.

Among the many unanswered questions in this ongoing exploration is why technology has not dramatically reduced the costs of the materials themselves. In other industries (computer hardware and software, music, automobiles, etc.) the introduction of technology has lead to falling prices (as compared to inflation) and rising functionality. This doesn't seem to be the case in textbooks, where price increases are surpassing inflation and the product is not getting dramatically better. It is enough to make one wonder if there is something special about the textbook ecosystem or if this is the result of inequitable market forces.

Extending the analogy between the textbook ecosystem and the music ecosystem, you may wonder if there is the equivalent to the Creative Commons activity of the latter. ((Creative Commons, for those that don't know, is the suite of activities that "that let authors, scientists, artists, and educators easily mark their creative work with the freedoms they want it to carry." For instance, a musician can mark their works in such a way as to be signal an allowance for others to use and reuse the material in a variety of ways without further permission or compensation.)) In fact, there is; such content is commonly called Open Textbooks or OpenCourseWare. The PIRG "Make Textbooks Affordable" campaign describes it this way: "Open textbooks are free, online, open-access textbooks. The content of open textbooks is licensed to allow anyone to use, download, customize, or print without expressed permission from the author." Others, such as Flat World Knowledge, seek new business models like giving away the content online and charging for derivatives such as audio formats, print, and study aids. [Update 20080710T0953 : An article from USA Today talks more about Flat World Knowledge and the concept of open textbooks.]

Your Thoughts

So this is how I've come to know the textbook ecosystem as a librarian peering into unfamiliar places and relationships. Is this how you see the marketplace as well? Whether your a Student, Instructor, or a representative from a Publisher, Bookstore or Used Textbook Wholesaler, I'm interested in your thoughts. Please send them to me privately (contact information) or publicly in the comment section of this entry.

Updates

Thursday, July 10, 2008: Nicole Allen, Textbooks Program Director at The Student PIRG, sent me an email where she lists two articles related to textbooks that were published in major newspapers today. First is As Textbooks Go 'Custom,' Students Pay from page D1 of today's Wall Street Journal. It describes another way that publishers deal with the used textbook market: custom publishing.

The University of Alabama, for instance, requires freshman composition students at its main campus to buy a $59.35 writing textbook titled "A Writer's Reference," by Diana Hacker. The spiral-bound book is nearly identical to the same "A Writer's Reference" that goes for $30 in the used-book market and costs about $54 new. The only difference in the Alabama version: a 32-page section describing the school's writing program -- which is available for free on the university's Web site. This version also has the University of Alabama's name printed across the top of the front cover, and a notice on the back that reads: "This book may not be bought or sold used."

The second is from USA Today entitled "Online 'textbooks' see college doors opening" and goes more in depth on the open textbook movement and the business model of Flat World Knowledge.

Friday, July 11, 2008: Even while this post was being conceived, news was spreading about an agreement between the Colorado Community College System and Pearson Education for flat pricing of digital textbook material. I found this via a convoluted path starting from a link that Lorcan Dempsey posted in a comment on this blog entry and ended up with a summary of the program posted on DLTJ.

Monday, August 16, 2010: Updated the link to the textbook piracy article from the Chronicle of Higher Education. Thanks for pointing out the broken link, Nathan G, and for suggesting the link on "The Truth About Textbook Piracy" from GuideToOnlineSchools.com.

The text was modified to remove a link to http://www.textbookfacts.org/media_1.htm on January 28th, 2011.

The text was modified to remove a link to http://www.nacs.org/newsroom/news/110907-coursesmart.asp on January 28th, 2011.

The text was modified to remove a link to http://www.nacs.org/newsroom/news/121407-coursesmart.asp on January 28th, 2011.

The text was modified to remove a link to http://saas.ica.washington.edu/academics/scholarships.aspx on January 28th, 2011.

The text was modified to update a link from http://www.flatworldknowledge.com/minisite/about.html to http://www.flatworldknowledge.com/about on January 28th, 2011.

The text was modified to remove a link to http://www.maketextbooksaffordable.org/statement.asp?id2=37614 on November 13th, 2012.

The text was modified to update a link from http://www.anotherbookstore.org/bundle.htm to http://web.archive.org/web/20080512144110/http://www.anotherbookstore.org/bundle.htm on November 13th, 2012.

The text was modified to update a link from http://www.forbes.com/finance/mktguideapps/personinfo/FromPersonIdPersonTearsheet.jhtml?passedPersonId=218341 to http://www.forbes.com/profile/leonard-riggio-1/ on November 13th, 2012.

The text was modified to remove a link to http://www.maketextbooksaffordable.org/statement.asp?id2=37633 on November 13th, 2012.

The text was modified to update a link from http://www.guidetoonlineschools.com/tips-and-tools/textbook-piracy to http://web.archive.org/web/20100806001040/http://www.guidetoonlineschools.com/tips-and-tools/textbook-piracy on November 19th, 2012.