- These list items are microformat entries and are hidden from view.

- https://dltj.org/article/snsi-webinar-thoughts/

Peter Murray

Peter Murray- Earlier this month, my Twitter timeline lit up with mentions of a half-day webinar called Cybersecurity Landscape - Protecting the Scholarly Infrastructure. What had riled up the people I follow on Twitter was the first presentation: “Security Collaboration for Library Resource Access” by Cory Roach, the chief information security officer at the University of Utah. Many of the tweets and articles linked in tweets were about a proposal for a new round of privacy-invading technology coming from content providers as a condition of libraries subscribing to publisher content. One of the voices that I trust was urging caution:I highly recommend you listen to the talk, which was given by a university CIO, and judge if this is a correct representation. FWIW, I attended the event and it is not what I took away.— Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe (@lisalibrarian) November 14, 2020As near as I can tell, much of the debate traces back to this article:Scientific publishers propose installing spyware in university libraries to protect copyrights - Coda Story https://t.co/rtCokIukBf— Open Access Tracking Project (@oatp) November 14, 2020The article describes Cory’s presentation this way:> One speaker proposed a novel tactic publishers could take to protect their intellectual property rights against data theft: introducing spyware into the proxy servers academic libraries use to allow access to their online services, such as publishers’ databases.The “spyware” moniker is quite scary.It is what made me want to seek out the recording from the webinar and hear the context around that proposal. My understanding (after watching the presentation) is that the proposal is not nearly as concerning.Although there is one problematic area—the correlation of patron identity with requested URLs—overall, what is described is a sound and common practice for securing web applications. To the extent that it is necessary to determine a user’s identity before allowing access to licensed content (an unfortunate necessity because of the state of scholarly publishing), this is an acceptable proposal.(Through the university communications office, Corey published a statement about the reaction to his talk.)In case you didn’t know, a web proxy server ensures the patron is part of the community of licensed users, and the publisher trusts requests that come through the web proxy server. The point of Cory’s presentation is that the username/password checking at the web proxy server is a weak form of access control that is subject to four problems: phishing (sending email to tricking a user into giving up their username/password) social engineering (non-email ways of tricking a user into giving up their username/password) credential reuse (systems that are vulnerable because the user used the same password in more than one place) hactivism (users that intentionally give out their username/password so others can access resources)Right after listing these four problems, Cory says: “But anyway we look at it, we can safely say that this is primarily a people problem and the technology alone is not going to solve that problem. Technology can help us take reasonable precautions… So long as the business model involves allowing access to the data that we’re providing and also trying to protect that same data, we’re unlikely to stop theft entirely.”His proposal is to place “reasonable precautions” in the web proxy server as it relates to the campus identity management system. This is a slide from his presentation: Slide from presentation by Cory Roach I find this layout (and lack of labels) somewhat confusing, so I re-imagined the diagram as this: Revised 'Modern Library Design' The core of Cory’s presentation is to add predictive analytics and per-user blocking automation to the analysis of the log files from the web proxy server and the identity management server. By doing so, the university can react quicker to compromised usernames and passwords. In fact, it could probably do so more quicker than the publisher could do with its own log analysis and reporting back to the university.Where Cory runs into trouble is this slide: <figcaption>Slide from presentation by Cory Roach</figcaption> In this part of the presentation, Cory describes the kinds of patron-identifying data that the university could-or-would collect and analyze to further the security effort. In search engine optimization, these sorts of data points are called “signals” and are used to improve the relevance of search results; perhaps there is an equivalent term in access control technology.But for now, I’ll just call them “signals”.There are some problems in gathering these signals—most notably the correlation between user identity and “URLs Requested”.In the presentation, he says: “You can also move over to behavioral stuff. So it could be, you know, why is a pharmacy major suddenly looking up a lot of material on astrophysics or why is a medical professional and a hospital suddenly interested in internal combustion. Things that just don’t line up and we can identify fishy behavior.”It is core to the library ethos that we make our best effort to not track what a user is interested in—to not build a profile of a user’s research unless they have explicitly opted into such data collection. As librarians, we need to gracefully describe this professional ethos and work that into the design of the systems used on campus (and at the publishers).Still, there is much to be said for using some of the other signals to analyze whether a particular request is from an authorized community member.For instance, Cory says: “We commonly see this user coming in from the US and today it’s coming in from Botswana. You know, has there been enough time that they could have traveled from the US to Botswana and actually be there? Have they ever access resources from that country before is there residents on record in that country?”The best part of what Cory is proposing is that the signals’ storage and processing is at the university and not at the publisher. I’m not sure if Cory knew this, but a recent version of EZProxy added a UsageLimit directive that builds in some of these capabilities. It can set per-user limits based on the number of page requests or the amount of downloaded information over a specified interval. One wonders if somewhere in OCLC’s development queue is the ability to detect IP addresses from multiple networks (geographic detection) and browser differences across a specified interval. Still, pushing this up to the university’s identity provider allows for a campus-wide view of the signals…not just the ones coming through the library.Also, in designing the system, there needs to be clarity about how the signals are analyzed and used. I think Cory knew this as well: “we do have to be careful about not building bias into the algorithms.”Yeah, the need for this technology sucks.Although it was the tweet to the Coda Story about the presentation that blew up, the thread of the story goes through TechDirt to a tangential paragraph from Netzpolitik in an article about Germany’s licensing struggle with Elsevier.With this heritage, any review of the webinar’s ideas are automatically tainted by the disdain the library community in general has towards Elsevier. It is reality—an unfortunate reality, in my opinion—that the traditional scholarly journal model has publishers exerting strong copyright protection on research and ideas behind paywalls. (Wouldn’t it be better if we poured the anti-piracy effort into improving scholarly communication tools in an Open Access world? Yes, but that isn’t the world we live in.) Almost every library deals with this friction by employing a web proxy server as an agent between the patron and the publisher’s content.The Netzpolitik article says: …but relies on spyware in the fight against „cybercrime“ Of Course, Sci-Hub and other shadow libraries are a thorn in Elsevier’s side. Since they have existed, libraries at universities and research institutions have been much less susceptible to blackmail. Their staff can continue their research even without a contract with Elsevier. Instead of offering transparent open access contracts with fair conditions, however, Elsevier has adopted a different strategy in the fight against shadow libraries. These are to be fought as „cybercrime“, if necessary also with technological means. Within the framework of the „Scholarly Networks Security Initiative (SNSI)“, which was founded together with other large publishers, Elsevier is campaigning for libraries to be upgraded with security technology. In a SNSI webinar entitled „Cybersecurity Landscape – Protecting the Scholarly Infrastructure“*, hosted by two high-ranking Elsevier managers, one speaker recommended that publishers develop their own proxy or a proxy plug-in for libraries to access more (usage) data („develop or subsidize a low cost proxy or a plug-in to existing proxies“). With the help of an „analysis engine“, not only could the location of access be better narrowed down, but biometric data (e.g. typing speed) or conspicuous usage patterns (e.g. a pharmacy student suddenly interested in astrophysics) could also be recorded. Any doubts that this software could also be used—if not primarily—against shadow libraries were dispelled by the next speaker. An ex-FBI analyst and IT security consultant spoke about the security risks associated with the use of Sci-Hub.The other commentary that I saw was along similar lines: [Is the SNSI the new PRISM? bjoern.brembs.blog](http://bjoern.brembs.net/2020/10/is-the-snsi-the-new-prism/) [Academics band together with publishers because access to research is a cybercrime chorasimilarity](https://chorasimilarity.wordpress.com/2020/11/14/academics-band-together-with-publishers-because-access-to-research-is-a-cybercrime/) [WHOIS behind SNSI & GetFTR? Motley Marginalia](https://csulb.edu/~ggardner/2020/11/16/snsi-getftr/) Let’s face it: any friction beyond follow-link-to-see-PDF is more friction than a researcher deserves. I doubt we would design a scholarly communication system this way were we to start from scratch. But the system is built on centuries of evolving practice, organizations, and companies. It really would be a better world if we didn’t have to spend time and money on scholarly publisher paywalls.And I’m grateful for the Open Access efforts that are pivoting scholarly communications into an open-to-all paradigm.That doesn’t negate the need to provide better options for content that must exist behind a paywall.So what is this SNSI thing?The webinar where Cory presented was the first mention I’d seen of a new group called the Scholarly Networks Security Initiative (SNSI). SNSI is the latest in a series of publisher-driven initiatives to reduce the paywall’s friction for paying users or library patrons coming from licensing institutions. GetFTR (my thoughts) and Seamless Access (my thoughts).(Disclosure: I’m serving on two working groups for Seamless Access that are focused on making it possible for libraries to sensibly and sanely integrate the goals of Seamless Access into campus technology and licensing contracts.)Interestingly, while the Seamless Access initiative is driven by a desire to eliminate web proxy servers, this SNSI presentation upgrades a library’s web proxy server and makes it a more central tool between the patron and the content.One might argue that all access on campus should come through the proxy server to benefit from this kind of access control approach.It kinda makes one wonder about the coordination of these efforts.Still, SNSI is on my radar now, and I think it will be interesting to see what the next events and publications are from this group.

- 2020-11-28T00:00:00+00:00

- 2020-11-30T19:49:40+00:00

User Behavior Access Controls at a Library Proxy Server are Okay

Earlier this month, my Twitter timeline lit up with mentions of a half-day webinar called Cybersecurity Landscape - Protecting the Scholarly Infrastructure. What had riled up the people I follow on Twitter was the first presentation: “Security Collaboration for Library Resource Access” by Cory Roach, the chief information security officer at the University of Utah. Many of the tweets and articles linked in tweets were about a proposal for a new round of privacy-invading technology coming from content providers as a condition of libraries subscribing to publisher content. One of the voices that I trust was urging caution:

I highly recommend you listen to the talk, which was given by a university CIO, and judge if this is a correct representation. FWIW, I attended the event and it is not what I took away.

— Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe (@lisalibrarian) November 14, 2020

As near as I can tell, much of the debate traces back to this article:

Scientific publishers propose installing spyware in university libraries to protect copyrights - Coda Story https://t.co/rtCokIukBf

— Open Access Tracking Project (@oatp) November 14, 2020

The article describes Cory’s presentation this way: > One speaker proposed a novel tactic publishers could take to protect their intellectual property rights against data theft: introducing spyware into the proxy servers academic libraries use to allow access to their online services, such as publishers’ databases.

The “spyware” moniker is quite scary. It is what made me want to seek out the recording from the webinar and hear the context around that proposal. My understanding (after watching the presentation) is that the proposal is not nearly as concerning. Although there is one problematic area—the correlation of patron identity with requested URLs—overall, what is described is a sound and common practice for securing web applications. To the extent that it is necessary to determine a user’s identity before allowing access to licensed content (an unfortunate necessity because of the state of scholarly publishing), this is an acceptable proposal. (Through the university communications office, Corey published a statement about the reaction to his talk.)

In case you didn’t know, a web proxy server ensures the patron is part of the community of licensed users, and the publisher trusts requests that come through the web proxy server. The point of Cory’s presentation is that the username/password checking at the web proxy server is a weak form of access control that is subject to four problems:

- phishing (sending email to tricking a user into giving up their username/password)

- social engineering (non-email ways of tricking a user into giving up their username/password)

- credential reuse (systems that are vulnerable because the user used the same password in more than one place)

- hactivism (users that intentionally give out their username/password so others can access resources)

Right after listing these four problems, Cory says: “But anyway we look at it, we can safely say that this is primarily a people problem and the technology alone is not going to solve that problem. Technology can help us take reasonable precautions… So long as the business model involves allowing access to the data that we’re providing and also trying to protect that same data, we’re unlikely to stop theft entirely.”

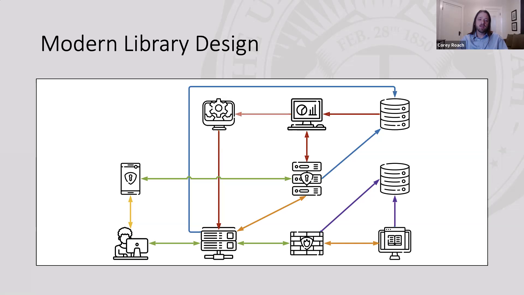

His proposal is to place “reasonable precautions” in the web proxy server as it relates to the campus identity management system. This is a slide from his presentation:

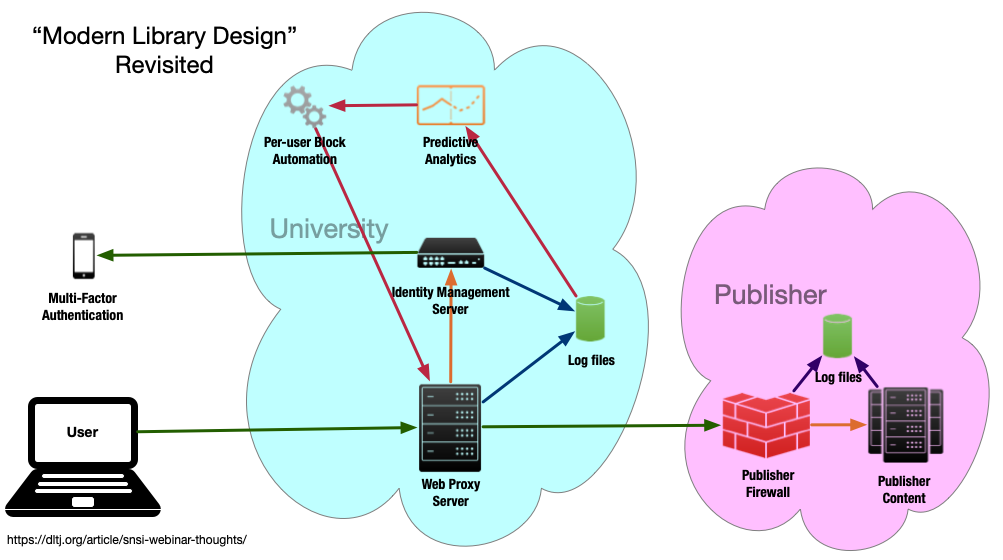

I find this layout (and lack of labels) somewhat confusing, so I re-imagined the diagram as this:

The core of Cory’s presentation is to add predictive analytics and per-user blocking automation to the analysis of the log files from the web proxy server and the identity management server. By doing so, the university can react quicker to compromised usernames and passwords. In fact, it could probably do so more quicker than the publisher could do with its own log analysis and reporting back to the university.

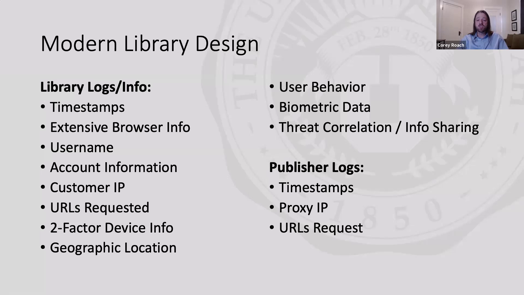

Where Cory runs into trouble is this slide:

<figcaption>Slide from presentation by Cory Roach</figcaption>

<figcaption>Slide from presentation by Cory Roach</figcaption>

In this part of the presentation, Cory describes the kinds of patron-identifying data that the university could-or-would collect and analyze to further the security effort. In search engine optimization, these sorts of data points are called “signals” and are used to improve the relevance of search results; perhaps there is an equivalent term in access control technology. But for now, I’ll just call them “signals”.

There are some problems in gathering these signals—most notably the correlation between user identity and “URLs Requested”. In the presentation, he says: “You can also move over to behavioral stuff. So it could be, you know, why is a pharmacy major suddenly looking up a lot of material on astrophysics or why is a medical professional and a hospital suddenly interested in internal combustion. Things that just don’t line up and we can identify fishy behavior.” It is core to the library ethos that we make our best effort to not track what a user is interested in—to not build a profile of a user’s research unless they have explicitly opted into such data collection. As librarians, we need to gracefully describe this professional ethos and work that into the design of the systems used on campus (and at the publishers).

Still, there is much to be said for using some of the other signals to analyze whether a particular request is from an authorized community member. For instance, Cory says: “We commonly see this user coming in from the US and today it’s coming in from Botswana. You know, has there been enough time that they could have traveled from the US to Botswana and actually be there? Have they ever access resources from that country before is there residents on record in that country?”

The best part of what Cory is proposing is that the signals’ storage and processing is at the university and not at the publisher.

I’m not sure if Cory knew this, but a recent version of EZProxy added a UsageLimit directive that builds in some of these capabilities.

It can set per-user limits based on the number of page requests or the amount of downloaded information over a specified interval.

One wonders if somewhere in OCLC’s development queue is the ability to detect IP addresses from multiple networks (geographic detection) and browser differences across a specified interval.

Still, pushing this up to the university’s identity provider allows for a campus-wide view of the signals…not just the ones coming through the library.

Also, in designing the system, there needs to be clarity about how the signals are analyzed and used. I think Cory knew this as well: “we do have to be careful about not building bias into the algorithms.”

Yeah, the need for this technology sucks.

Although it was the tweet to the Coda Story about the presentation that blew up, the thread of the story goes through TechDirt to a tangential paragraph from Netzpolitik in an article about Germany’s licensing struggle with Elsevier.

With this heritage, any review of the webinar’s ideas are automatically tainted by the disdain the library community in general has towards Elsevier. It is reality—an unfortunate reality, in my opinion—that the traditional scholarly journal model has publishers exerting strong copyright protection on research and ideas behind paywalls. (Wouldn’t it be better if we poured the anti-piracy effort into improving scholarly communication tools in an Open Access world? Yes, but that isn’t the world we live in.) Almost every library deals with this friction by employing a web proxy server as an agent between the patron and the publisher’s content.

The Netzpolitik article says:

…but relies on spyware in the fight against „cybercrime“

Of Course, Sci-Hub and other shadow libraries are a thorn in Elsevier’s side. Since they have existed, libraries at universities and research institutions have been much less susceptible to blackmail. Their staff can continue their research even without a contract with Elsevier.

Instead of offering transparent open access contracts with fair conditions, however, Elsevier has adopted a different strategy in the fight against shadow libraries. These are to be fought as „cybercrime“, if necessary also with technological means. Within the framework of the „Scholarly Networks Security Initiative (SNSI)“, which was founded together with other large publishers, Elsevier is campaigning for libraries to be upgraded with security technology. In a SNSI webinar entitled „Cybersecurity Landscape – Protecting the Scholarly Infrastructure“*, hosted by two high-ranking Elsevier managers, one speaker recommended that publishers develop their own proxy or a proxy plug-in for libraries to access more (usage) data („develop or subsidize a low cost proxy or a plug-in to existing proxies“).

With the help of an „analysis engine“, not only could the location of access be better narrowed down, but biometric data (e.g. typing speed) or conspicuous usage patterns (e.g. a pharmacy student suddenly interested in astrophysics) could also be recorded. Any doubts that this software could also be used—if not primarily—against shadow libraries were dispelled by the next speaker. An ex-FBI analyst and IT security consultant spoke about the security risks associated with the use of Sci-Hub.

The other commentary that I saw was along similar lines:

-

[Is the SNSI the new PRISM? bjoern.brembs.blog](http://bjoern.brembs.net/2020/10/is-the-snsi-the-new-prism/) -

[Academics band together with publishers because access to research is a cybercrime chorasimilarity](https://chorasimilarity.wordpress.com/2020/11/14/academics-band-together-with-publishers-because-access-to-research-is-a-cybercrime/) -

[WHOIS behind SNSI & GetFTR? Motley Marginalia](https://csulb.edu/~ggardner/2020/11/16/snsi-getftr/)

Let’s face it: any friction beyond follow-link-to-see-PDF is more friction than a researcher deserves. I doubt we would design a scholarly communication system this way were we to start from scratch. But the system is built on centuries of evolving practice, organizations, and companies. It really would be a better world if we didn’t have to spend time and money on scholarly publisher paywalls. And I’m grateful for the Open Access efforts that are pivoting scholarly communications into an open-to-all paradigm. That doesn’t negate the need to provide better options for content that must exist behind a paywall.

So what is this SNSI thing?

The webinar where Cory presented was the first mention I’d seen of a new group called the Scholarly Networks Security Initiative (SNSI). SNSI is the latest in a series of publisher-driven initiatives to reduce the paywall’s friction for paying users or library patrons coming from licensing institutions. GetFTR (my thoughts) and Seamless Access (my thoughts). (Disclosure: I’m serving on two working groups for Seamless Access that are focused on making it possible for libraries to sensibly and sanely integrate the goals of Seamless Access into campus technology and licensing contracts.)

Interestingly, while the Seamless Access initiative is driven by a desire to eliminate web proxy servers, this SNSI presentation upgrades a library’s web proxy server and makes it a more central tool between the patron and the content. One might argue that all access on campus should come through the proxy server to benefit from this kind of access control approach. It kinda makes one wonder about the coordination of these efforts. Still, SNSI is on my radar now, and I think it will be interesting to see what the next events and publications are from this group.